A Method of Reducing Violent Crime

|

|

The concept of expected value can be used to predict future events or a person's future actions. The expected value of an event is the value of the event if it occurs multiplied by the probability that it will do so. For example, if there is a "one in a million" chance of winning a million dollar lottery, the expected value of a ticket is one dollar. Thus, it makes sense to pay not more than that. Lottery gamblers bet more than the expected value of their prizes. They lose money to the lottery, which is how it makes so much profit no matter how much it pays out in winnings.

Expected values can be assigned to things that seem totally unpredictable. For example, while it is impossible to predict whether any particular individual will attend a rock concert, it is definitely possible to assign an expected value to the number of attendees. Multiplying this value by the cost of each ticket determines how much the sponsor can expect to make, and thus how much he can afford to spend to book the concert in the first place and still make money. His degree of confidence in his prediction, called confidence level, is between zero and one (100%), and increases as the number of tickets sold. For promoters who sponsor thousands of concerts with millions of attendees, the confidence level becomes very close to 100%, that is, virtually certain.

This same computation gives society an opportunity to identify people who may become capital criminals in the future. Very few people lead a blameless life before committing a capital felony. Most major criminals work up to a capital crime by committing a series of more and more grievous crimes, sometimes being convicted and punished for them, sometimes not. As a simplified example, if it is known that a certain percentage (P) of felons who are convicted of a less serious crime historically commit one or more murders, we can say with a known level of confidence that of all persons convicted of the less serious crime, P of them will eventually commit murder or, alternately, that there is a probability that any given person convicted of the lesser crime will go on to commit P murders. Similar computations, given a felon's past convictions, can predict, with any specified level of confidence, how many victims he will murder in the future if conditions don't change.

The conditions are those applying to past criminals. Petty criminals pay fines, do community service, and spend time under house arrest or in jail, but they can eventually expect release. Even "life imprisonment" does not automatically mean a convict will die in prison. "Lifers" have their sentences reversed, are pardoned, escape, and commit horrible crimes, sometimes even aggravated first degree murder, against guards and other inmates. Whole prisons full of them vanish or are simply released to rape, murder, pillage and plunder during earthquakes and floods. Popular sentiment suggests that once a prisoner has "served his sentence," he has "paid his debt to society" and should go free to commit other crimes. We do not ordinarily think of people convicted of petty theft or simple burglary as being potential murderers, but, scientifically, it is possible to predict that such people will murder a certain number of victims, although for only petty criminals that number would be calculated to be less than one.

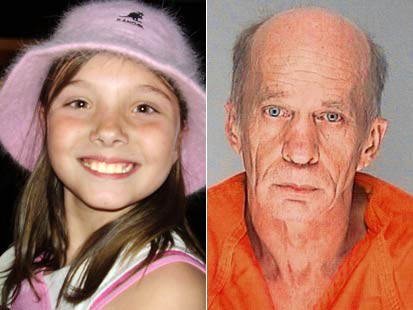

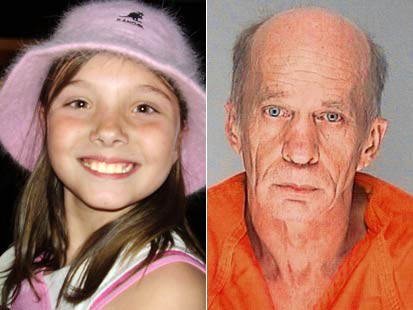

The idea of predicting a murder of less than one victim may be difficult to grasp, but the calculated number of future murders (and murder victims) increases as the number of lesser crimes and P increases. A probability is not a guess, it is a mathematical variable that can be calculated with precision. It is science, the same science that allows insurance companies to make money by predicting when any given client is going to die. Likewise, the victims are not faceless statistics. They are actual people, actually dead, sometimes horribly, from the intentional acts of actual criminals. In the case where P is "half a victim," this means that for a large number of criminals, 50% of them will commit murder and 50% won't. We just don't know which ones will be the murderers. We don't know who the victims will be either, but we do know with measurable confidence how many actual victims will actually die at their hands. We know who they are only after they're dead: Jessica Lunsford. Shakira Johnson. JonBenet Ramsey. Ashley Pond. Miranda Diane Gaddis. Paulette Crickmore. Derrick Robie. Jessica Chapman. Holly Wells. Danielle van Dam. Samantha Runnion. Michelle Vick. Martha Moxley. Sarah Hajney. Jen Boldu. Katie Savino. Christina Long. Amanda Brown. Ashley Mance. Joseph Barefoot. Sherrice Iverson. Jeffrey Curley. Nicole Parker. Steve Branch. Michael Moore. Chris Byers. Cary Ann Medlin. Patty Rebholz. Shaniya Davis. Somer Thompson. Wyatt Thomas Smitsky. Sandra Cantu. Chelsea King. Amber Dubois. Etc. Etc. Etc.

It is never possible to be absolutely certain that someone already committed a crime, let alone that he's going to do so in the future. However, neither conviction of nor sentencing for capital crimes in the United States requires absolute certainty (a confidence level of 100%), only certainty "beyond a reasonable doubt." A reasonable doubt is one for which a reason can be given. Mathematically, it is a "high" confidence level. What "reason" and "high" mean in this context is left up to the conscience of each individual juror, but a juror who admits to requiring absolute certainty is not allowed to serve on a real jury. If we compile a database of criminals and their crimes, it is possible to predict far beyond a "reasonable doubt" how many murders any convict is expected to commit. The same is true for any other crimes.

Of course, if it is known that a convict has already committed a crime, the number of victims of that crime is certainly at least one. Based on known, historical, actual data, we can calculate exactly how confident we can be that he will commit another - and another - and another!

There are serious Fourth Amendment issues involved in trying to predict if a given person is likely to commit a serious crime, which is probably one of the reasons that such a means does not now exist. However, at least one algorithm already exists that is claimed to predict, with 80 to 90 percent accuracy, when and where, within a narrow window, sombody is likely to commit a given crime. The police may not now be allowed under the Constitution to follow an unindicted person around to nab him when he commits a crime, but they can be directed to locations where he is likely to show up to commit it!

The number of violent crimes committed each year in the United States is truly astounding! According to the Statistical Abstract of the United States, every year from 1990 to 2000, approximately 21,800 people were murdered, 101,100 were forcibly raped, 593,000 were robbed, and 1,073,000 were victims of aggravated assault. Yet, in this entire nine years, only 380 convicts were put to death in the United States, all of them for murder. During that decade, for every 107 people who died, one person was murdered, over four were raped, 27 were robbed, and almost half were feloniously assaulted!

| Victims of Violent Crimes (from Statistical Abstract of the United States - 2000, Table 219) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Number of offenses x 1,000 | Rate per 100,000 population: | Murderers Executed | ||||||||

| Total victims | Murder | Forcible rape | Robbery | Aggravated assault | Murder | Forcible rape | Robbery | Aggravated assault | Number | Percent (of all the murders that year) | |

| 1990 | 1,820 | 23.4 | 102.6 | 639 | 1,055 | 9.4 | 41.2 | 257.0 | 424.1 | 23 | 0.000126 |

| 1991 | 1,912 | 24.7 | 106.6 | 688 | 1,093 | 9.8 | 42.3 | 272.7 | 433.3 | 14 | 0.000073 |

| 1992 | 1,932 | 23.8 | 109.1 | 672 | 1,127 | 9.3 | 42.8 | 263.6 | 441.8 | 31 | 0.000160 |

| 1993 | 1,926 | 24.5 | 106.0 | 660 | 1,136 | 9.5 | 41.1 | 255.9 | 440.3 | 38 | 0.000197 |

| 1994 | 1,858 | 23.3 | 102.2 | 619 | 1,113 | 9.0 | 39.3 | 237.7 | 427.6 | 31 | 0.000167 |

| 1995 | 1,799 | 21.6 | 97.5 | 581 | 1,099 | 8.2 | 37.1 | 220.9 | 418.3 | 56 | 0.000311 |

| 1996 | 1,689 | 19.7 | 96.3 | 536 | 1,037 | 7.4 | 36.3 | 201.9 | 390.9 | 45 | 0.000266 |

| 1997 | 1,636 | 18.2 | 96.2 | 499 | 1,023 | 6.8 | 35.9 | 186.3 | 382.3 | 74 | 0.000452 |

| 1998 | 1,531 | 16.9 | 93.1 | 447 | 974 | 6.3 | 34.4 | 165.2 | 360.5 | 68 | 0.000444 |

| Mean | 1,789 | 21.8 | 101.1 | 593 | 1,073 | 8.4 | 38.9 | 229.0 | 413.2 | 42 | 0.000244 |

| Causes of Death (from Statistical Abstract of the United States - 2000, Table 126) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Deaths x 1,000 | Crude death rate per 100,000 population | ||||||

| 1990 | 1995 | 1997 | 1998 | 1990 | 1995 | 1997 | 1998 | |

| All causes | 2,148.5 | 2,312.1 | 2,314.2 | 2,338.1 | 863.8 | 880.0 | 864.7 | 865.0 |

| Suicide | 30.9 | 31.3 | 30.5 | 29.3 | 12.4 | 11.9 | 11.4 | 10.8 |

| Homicide and legal intervention | 24.9 | 22.9 | 19.8 | 17.4 | 10.0 | 8.7 | 7.4 | 6.4 |

Among the functions of government in the United States are the establishment of justice, insuring domestic tranquility, providing for the common defense, promoting the general welfare, and securing liberty for its citizens. These purposes cannot be accomplished if the public is constantly at mortal risk from dangerous criminals. Therefore, government has a right and duty to render unable to cause harm those known to be a threat of doing so.

It is important to remember that the threat does not arise from the individual's past victimization of others or destruction of property. For example, citizens are encouraged to do these things, and even praised for doing them in a military conflict. The threat posed by the murderer or rapist consists specifically and totally in the fact that murder and rape are unlawful in a society which has defined acceptable behavior according to its laws. The fact that a criminal has demonstrated his refusal to obey the law in the past is a far more reliable indicator of his ultimate threat to society than the nature of the specific laws he has chosen to disregard.

The efforts of the state to curb the spread of behavior harmful to people's rights and to the basic rules of civil society, that is, to obey the law, also correspond to the requirement of safeguarding the common good. Therefore, civil authority has the right and the duty to inflict punishment proportionate to the gravity of civil offenses with a view to redressing the disorder introduced by the offense and correction of the behavior of the guilty party. But punishment is a disincentive for unlawful behavior, not prevention. For example, fines for illegal parking, in addition to paying for the police personnel and enforcement activities involved, can reduce to a tolerable level the number of violations by making the consequences worse than foregoing whatever the advantages of committing them are.

That there is a "tolerable level" of murders, rapes, robberies, aggravated assaults and other violent and unlawful behaviors in US society is far from a foregone conclusion. The fact that over 519 times as many citizens are murdered (and 42,079 times as many others are raped, robbed or assaulted) by perpetrators than perpetrators are put to death by society every year demonstrates that society overwhelmingly (in a ratio of 42,598 to 1!) jeopardizes the peaceful lives of the innocent by protecting the guilty and allowing their unlawful behavior to continue. Given that the future commission of crimes by those already convicted of others can be scientifically and precisely predicted, it does not seem logical either to use only measures of prevention conclusively demonstrated to be ineffective, or to wait until the felon has already committed a specific capital crime to employ them. The sad fact is that the state has only the possibility of diminishing the incidence of crime, not for effectively preventing it. Even in a maximum security prison, it is simply not possible to render an inmate incapable of doing harm or to defend and protect the safety of the staff and other inmates by nonlethal means. The only possible way of effectively defending human lives against the truly dedicated unjust aggressor is positively to eliminate him.

We are doing the opposite of that now. The one unifying experience of the human race, righteous and unrighteous alike, is death! Yet, we impose that as a penalty for only the worst crimes that it is possible to commit, and we also wait until somebody has committed one before doing that! Then we exonerate him if he is found to be so dangerous that he is not responsible for his actions. Even if we do decide permanently to get rid of him, we feed, clothe, house, educate and entertain him for decades while we dither about it. If he has made our society safe by escaping to someplace else, we spend millions of dollars to bring him back so we can begin the dithering process! We even make it a crime for somebody to go to Syria or someplace to be a suicide bomber, instead of just revoking his passport and letting nature take its course. There has to be a better way!

The efforts of the state to safeguard the common good would suggest that punishment proportionate to the gravity of civil offenses and redressing the disorder introduced by them would involve eliminating roughly the same number of known dangerous felons every year as the number of their victims, for the purpose of reducing the total number of victims (including the perpetrators) of violent crime. One could logically begin by removing from society all those who have actually committed one or more murders, and then continue with those whose established history of lesser crimes demonstrated an unacceptable number of expected victims. The efficacy of this practice could be validated in just a few months as the total number of victims (including those eliminated) began to decline. The goal would be to reach a point at which the combined total of innocent victims and known dangerous felons removed from society reached a minimum.

It is important to realize that the decline in the number of victims is not simply a statistic; it is an actual number of people who are not murdered, raped, robbed or assaulted. It is a actual number of actual little girls who are not sold into prostitution and then fatally strangled or bludgeoned almost to death and then buried while they're in the process of dying. If last month there were more of these atrocities than there are this month, the right things are being done, however we might deplore their necessity.

I think it is important to make a distinction between "penalty" and "prevention." What is called "criminal justice" in the United States is strongly influenced by Quaker philosophy that people are basically good, and that if they are made to contemplate the evil of their past actions long enough, such as in prison, they will eventually change their ways. Gradually, prison was seen as place where criminals were reformed by being subjected to deprivation of their liberty and possibly harsh treatment, the most harsh of which, was being put to death.

The problem is, deprivation of liberty, harsh treatment within the limitations of the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, and even the threat and eventual execution of the death penalty have no demonstrably significant effect on the prevention of crime, especially in the United States, where about one in 148 people is in jail or prison. The penalty is imposed only after, not before, the convict commits a crime, and often not then.

For this reason, I am not comfortable with any "penalty" for felonies generally. I think protection of society from dangerous criminals, is a worthwhile goal, but I don't see how waiting until someone has already committed a crime does that. I simply do not know what any convicted criminal "deserves," regardless of his crime, and I do not believe that any crime, especially one that harms a fellow human being, can be "undone," regardless of what is imposed on someone after he commits it. Even for capital crimes, the "death penalty" in the United States doesn't seem to be doing much good. For one thing, it takes too long, costs too much, and doesn't prevent the crime for which it is imposed or keep others, or even somebody who has "gotten away with it," from committing the same one again. There has to be a better way!

I submit that it is in the best interests of all concerned if juries are given sole authority for disposition of the convict, within legally specified limits. These might include the option of a conditional sentence. After examining the circumstances of the crime and the nature of the criminal, a scientific determination could be made, by recognized forensic psychologists and statisticians, of the danger a convict poses to society. Where this danger is unacceptably great, the jury should have the option of positively removing him from society and recognizing that the presumption of innocence has already been overcome. This sentence would be imposed for having already proved by his past actions that he is an unacceptable risk to society. Perhaps someone more knowledgeable than I am in criminal behavior and rehabilitation potential could suggest ways and means of doing this.

This option for sentencing would be for the jury to have the sole discretion of how best to eliminate the criminal from society, given the Constitutional prohibition against "cruel or unusual punishment." This discretion could allow the jury to make a deal with the convict, for example, to renounce his citizenship, forfeit all or part of his property to the state, and voluntarily move to any country that would accept (or could be persuaded to take) him. The purpose would be to remove the threat the convict poses to the society that sentences him. If another society considers him worth saving, everyone benefits by the transfer. And if the individual thereafter commits what that society thinks is a crime, what happens to him then is simply not our responsibility.

To be specific, I would be in favor of the passage of laws essentially like the following:

This proposal is fundamentally different from punishment. It does not seek resolution of public outrage, retribution, vengeance, redressing social injury, inflicting evil so that good may come of it, making a sinner suffer, or paying some kind of "debt to society." It is certainly not "tit for tat," or "an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth." It is the use of science, one of mankind's most sublime activities, to protect, as much as possible, the lives of innocent people who would otherwise be unjustly and irreparably harmed, or abruptly terminated, by deliberate acts of the most profound cruelty; especially to children, who accounted for 9.4% of all murder victims in the US in 2005, according to a FBI Report.

Of course, this idea could work the other way, too. If the jury has the authority to determine the disposition of the convict, it can use that authority to tailor its response to those who are convicted of crimes of passion, diminished capacity, or simple stupidity. In many cases, these criminals become convinced of the impropriety of their actions virtually instantly afterward. Why should they, and society, be burdened with caring for them when they are no more a threat than anyone else, and could be gainfully employed and paying taxes? Instead of putting in prison a compassionate and loving adult who regretfully grants a terminally ill spouse's wish to die and be relieved from intolerable suffering, the jury could sentence him to helpful counseling and eventually let him go. If the jury, not some legislator in Washington, gets to determine the appropriate response to antisocial behavior, the society in which the jury lives is likely most to benefit.

A rough parallel can be drawn between treatment of dangerous criminals and war, the legitimacy of which can be justified only if the expected value of the benefits is significantly greater than the expected value of undesired consequences. As an example, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki resulted in the deaths of about 200,000 people. However, it quickly ended the war, saving an estimated 1,000,000 American and 1,000,000 Japanese military who would have been killed in the invasion, 250,000 Allied prisoners of war, and 5,000,000 Japanese civilians who would have starved to death while their country was still fighting. The bombing saved 7,050,000 lives, at the cost of 200,000, less than three percent of that total. That is why its use is historically and morally justified!

I believe that treating dangerous felons the same way would manifest our belief in the unique worth and dignity of each person and the testimony of our society to belief in the essential sanctity of life. It would offer to every criminal the possibility for reform and rehabilitation, allow him to make some creative compensation for the evil of his past crimes, minimize the possibility of mistake, avoid long delays, provide an opportunity to diminish the anguish for the criminal and those who care about him, reduce public controversy, and treat racial minorities and the poor more equitably.

The United States is not fulfilling the purposes enumerated in its Constitution by exposing innocent victims, especially children and the elderly, to predation by vicious criminals. The Founding Fathers wanted us to be better than that! We have an obligation, as their posterity, to live up to their sacred trust in us, for which they gave their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor.

Notwithstanding any other law or regulation, the jury which convicts any person of a felony shall have sole and absolute descretion regarding the punishment or disposition, within legislatively specified limits, of the convict. Such jury shall have the additional option to impose other conditions, with the irrevocable consent of the convict, as an alternative to punishment.

This might make it easier to try a suspect in absentia. He has a right, among others, to be confronted with witnesses against him, but he does not have any obligation to examine them. All of his constitutional rights appear to be respected if a scheduled speedy and public trial is held, where the clearly explained charges are presented by a grand jury, and the accused is represented by competent counsel. The accused does not have to show up. Appeals could be conducted with sufficient time and publicity to give him a chance to participate. If the convict is later apprehended, he could be given the opportunity for a final hearing (to explain, among other things, why he didn't attend the earlier ones) and then, unless reversed, the sentence imposed by the original jury could be swiftly carried out, (possibly in the process of resisting arrest). If the convict is never caught, good riddance! This situation would give convicts of serious crimes a powerful incentive never to be heard from again!