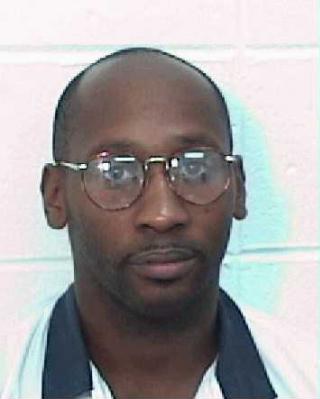

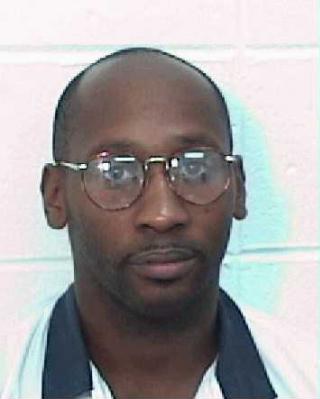

The Troy Davis Case

|

| Troy Davis, who was convicted of, and put to death for, the crime of murder with aggravating factor |

|---|

|

| Troy Davis, who was convicted of, and put to death for, the crime of murder with aggravating factor |

|---|

About nine years earlier than Mr. Byrd's murder, on August 19, 1989 in Savannah, Georgia, Troy Davis shot Michael Cooper and later shot and killed off-duty police officer Mark MacPhail. MacPhail was working as a security guard at a Burger King restaurant when he intervened to defend Larry Young, who was being assaulted by Davis and others in a nearby parking lot. On September 21, 2011, the same day as the execution of Brewer's death sentence, Davis was also put to death by lethal injection, at the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification State Prison in Butts County, Georgia.

Except for a brief revival of the facts of the case in the news media just before execution of his sentence, and the anomaly of ordering a huge "last meal" that he didn't eat, Brewer's demise went largely unnoticed. Opposition to Davis' sentence, on the other hand, was so extensive and emotional that riot police were present to control the mourners and demonstrators. Nearly one million people signed petitions in an unsuccessful attempt to pressure the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles to grant clemency, which, refusing to cave to public opinion, it denied. Davis maintained his innocence to the very end.

A lot of people saw significance in the color of the individuals involved. MacPhail and Brewer were white, Davis and Byrd were black. The consensus seemed to be that Brewer, a known white supremacist, deserved death only because it was the most severe penalty that Texas could impose, while Davis was widely thought to have been a victim of "the system," wrongly convicted and put to death because of his color. Famous people, including former President Jimmy Carter, Al Sharpton, Pope Benedict XVI, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, former Congressman Bob Barr, and former FBI Director William S. Sessions called upon the courts to grant Davis a new trial or another evidentiary hearing. None of them were present at the crime scene or the investigation, or the trial, and so had less knowledge of the case than the witnesses, investigators, or jury.

The facts do not support their reasoning. According to information complied and referenced by Wikipedia, Davis and a friend, Darrel Collins, were both present when Michael Cooper was shot in the face with a weapon found to be of the same caliber that killed MacPhail a short time later. Trial witnesses Harriet Murray, Redd Coles (who reported the murder to the police the same day), Dorothy Ferrell, Larry Young (the assault victim), and Antoine Williams testified that Davis, wearing a white shirt, had struck Young and then shot MacPhail with a pistol. Both Murray and Ferrell told jurors that Davis shot again after MacPhail fell to the ground wounded. Witness Steven Sanders identified Davis as MacPhail's murderer. A neighbor of the Davis family, Jeffrey Sapp, testified that soon after the murder, Davis had confessed the crime to him. Kevin McQueen, a former fellow prisoner, testified that Davis had stated that he had killed the officer because he had feared that MacPhail would connect him to the earlier shooting. Davis pled "not guilty." He claimed that he left the scene of Young's assault before any shots were fired and did not know who had killed MacPhail.

In the United States, Amendment IV to the Constitution prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures. Search warrants require probable cause, support by oath or affirmation, and description of the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V provides that no person shall be held to answer for a capital crime in a civilian trial except upon indictment by grand jury, and shall not be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law, or be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb or compelled to be a witness against himself.

Amendment VI requires that in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district in which the crime was committed, to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation, to be confronted with the witnesses against him, to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

Amendment VII provides that no fact tried by a jury shall be otherwise reexamined in any court of the Unites States than according to the rule of common law.

Amendment VIII prohibits excessive bail or cruel and unusual punishments.

Amendment XIV prohibits any state from making or enforcing any law that abridges the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States, or to deny any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

In addition, criminal trials in every state in the United States require presumption of innocence and proof of guilt "beyond a reasonable doubt," Coffin v. United States 156 U.S. 432 (1895). What is "reasonable" is up to the conscience of each individual juror. The prosecution presents only lawfully admissible evidence that a crime was committed and the accused committed it. The defense attempts to cast doubt on one or both of those allegations. The jury decides if the burden of proof "beyond a reasonable doubt" has been met by the prosecution. The Judge maintains order and assures that requirements of the law are enforced.

The phrase, "life, liberty, or property without due process of law" in Amendments V and XIV is generally considered authority for the United States and individual states to impose the penalty of death. In Gregg v. Georgia, Proffitt v. Florida, Jurek v. Texas, Woodson v. North Carolina, and Roberts v. Louisiana, the United States Supreme Court reaffirmed acceptance of the use of the death penalty in the United States, and set forth the two main features that capital sentencing procedures must employ to meet the Amendment VIII bar on "cruel and unusual punishments."

First, objective criteria must direct and limit the death sentencing discretion. The objectiveness of these criteria must be ensured by appellate review of all death sentences.The Court prohibited the death penalty for rape (Coker v. Georgia), restricted it in cases of felony murder (Enmund v. Florida), exempted the mentally handicapped (Atkins v. Virginia) and juvenile murderers (Roper v. Simmons) from the death penalty, removed virtually all limitations on the presentation of mitigating evidence (Lockett v. Ohio, Holmes v. South Carolina), required precision in the definition of aggravating factors (Godfrey v. Georgia, Walton v. Arizona), and required the jury to decide whether aggravating factors have been proved beyond a reasonable doubt (Ring v. Arizona).

Ring v. Arizona is particularly important because the Court ruled that a jury must find the aggravating factors necessary for imposing the death penalty. This case overruled a portion of Walton v. Arizona and the provisions of Spaziano v. Florida that allowed a judge to impose a death sentence, overriding a jury's recommendation of life imprisonment.

All of these requirements must be met for the convict to be put to death. The various states have additional requirements, but Amendment XIV applies in all cases.

It is important to note that in jury trials, the jury, not the judge, is responsible for determining whether or not the defendant is guilty. In some jurisdictions, the jury decides punishment, in others the judge does so, but he cannot impose a sentence more severe than that recommended by the jury. In all cases, the judge (not the jury), is there to make sure that the law is followed by everyone involved in the trial and that the defendant's rights are upheld.

Capital felony trials begin with a process known as voir dire. Prospective jurors are questioned about their backgrounds and prejudices before being chosen to sit on a jury, and expert witnesses are questioned about their histories and qualifications before being allowed to present their testimony in court. The process assures, as far as possible, that jurors are likely to be fair and impartial, and that expert witnesses are, in fact, experts. People called as jurors may be rejected by either the prosecution or defense for cause, and both sides are allowed a certain number of preemptory challenges, the reasons for which are not required to be disclosed.

In addition, potential witnesses are examined so that both sides understand their qualifications and credibility, and can prepare to question (cross examine) their testimony under oath. All evidence to be presented is examined for admissibility and relevance, and unlawful evidence is excluded from presentation.

Such was the case of Troy Davis. According to Wikipedia, on November 15, 1989, a grand jury indicted Davis for murder, assaulting Larry Young with a pistol, shooting Michael Cooper, obstructing MacPhail in performance of his duty, and possession of a firearm during the commission of a crime. Davis pleaded not guilty on April 30, 1990. Trial was set for October, but was postponed by defense lawyers for a psychological evaluation.

Six days previously, Judge James W. Head banned incriminating evidence (bloody shorts) seized during a search of the home of Davis' mother, ruling that a search warrant should have been obtained. Prosecutors appealed the ruling to the Georgia Supreme Court, which ruled in May, 1991, that Judge Head was correct. The improperly obtained evidence was not presented at trial.

Davis' trial began August 20, 1991, and lasted to August 28. The Jury, after hearing all the evidence presented by the prosecution and defense, including testimony and cross examination of witnesses and Davis' own testimony, took two hours, a remarkably short time, to convict him of murder. Two days later, after seven hours, the jury sentenced him to death. On October 1, his lawyers filed a motion for a new trial. They presented their arguments on February 18, 1992. After consideration, Judge Head upheld the conviction and sentence.

Both the conviction and sentence were appealed automatically to the Georgia Supreme Court. A new trial was requested, based on selection of the original trial site and the jury, including its mostly black racial composition, and allegation that Davis' lawyers did not provide effective counsel. The request for a new trial was denied in March 1992 and the conviction and sentence were upheld a year later. The US Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal in November 1, 1993.

It is perhaps germane to point out that the purpose of the automatic appeal is not to "second guess" the jury. The jury determines facts (was Larry Young assaulted with a pistol, did Davis do it, did he shoot Michael Cooper, did he obstruct MacPhail in performance of his duty, did MacPhail die as a result of being shot by Davis, and did Davis possess a firearm during the commission of a crime?). The defendant must be presumed innocent unless and until the jury decides that such presumption is overcome "beyond a reasonable doubt," that is, a doubt for which a reason can be demonstrated. The jury is accountable only to itself, not to the judge, public opinion or the news media. The appeal process examines whether or not the law was followed during the trial, not whether the jury was right or wrong. The Georgia Supreme Court determined that the law was followed, and the US Supreme Court let that decision stand.

Following the completion of the appeal process, March 3, 1994, Judge Head signed the first order for execution of the sentence. It ended Davis' rounds of direct appeals to his conviction. However, his attorneys filed several habeas corpus proceedings. These alleged wrongful imprisonment on a variety of grounds. Davis claimed that he had been wrongfully convicted, that his death sentence was a miscarriage of justice, that the Georgia Resource Center, which helped represent him, didn't do an acceptable job, that there were numerous witnesses that should have been interviewed but were not, that the testimony of the prosecution witnesses had been coerced by law enforcement personnel, and that the use of the electric chair during death sentence executions in Georgia constituted cruel and unusual punishment. (Davis was eventually put to death by lethal injection.)

In 1996, after the Oklahoma City bombing, Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996. This act bars death row inmates from later presenting evidence they could have presented at trial. Davis' petition was denied in September 1997, with the court ruling that the claims should have been presented for examination to the jury to evaluate during the trial. (It should be noted that Davis could have raised these issues himself during his testimony, but did not.) The Georgia Supreme Court affirmed the denial of state habeas corpus relief on November 13, 2000.

In December 2001, Davis' attorneys filed a habeas corpus petition in the United States District Court on the assertion that several witnesses had changed or recanted their testimony, and that three of them had signed affidavits that Redd Coles, who had reported the shooting of MacPhail to the police, had confessed the murder to them. Davis' supporters considered this a major issue, but in fact, it was not. With time, witnesses' memories become confused, they may be coerced or convinced by others, or they may claim to have lied on the witness stand. In the latter case, the changed testimony is proof positive that the witness is a liar in one instance or the other. The purpose of cross examination during the trial is to expose such lies to the jury, which is the final arbiter of whether the witness is telling the truth or not. No such opportunity is given for recanted testimony, so whatever the witness claims later only rarely, and then only under unique circumstances, overcomes whatever he said during the trial.

This does not mean that the accused cannot present new evidence or testimony, only that, once he is declared guilty by a jury, he is presumed actually to be guilty. Evidence for a reversal of this finding must be a clear and convincing demonstration of his innocence, not baseless excuses about why he was convicted.

(Actually, the reason that appeals focus on the lawfulness of the conviction is that there is no demonstrated Constitutional requirement for the lawful conviction of a felon to be overturned even if absolute, positive proof is later presented of his innocence! The Supreme Court has traditionally presumed that there is without ruling on the issue one way or the other. This consideration did not apply in Davis' case, however, because he didn't have any such proof.)

The United States District Court found that the submitted affidavits did not demonstrate that the law was not followed during the trial. It also rejected other defense contentions about unfair jury selection, ineffective defense counsel and prosecutorial misconduct, none of which demonstrated conclusively that Davis had not, in fact, committed the crimes of which he was convicted by the jury. The decision was appealed to the 11th Circuit Court, which heard oral arguments in the case in September 2005. On September 26, 2006, the court affirmed the denial of federal habeas corpus relief, and determined that Davis had not made "a substantive claim of actual innocence" or shown that his trial was constitutionally unfair. The court also found that neither prosecutors nor defense counsel had acted improperly or incompetently at trial. A petition for panel rehearing (with the full court in session) was denied in December 2006.

On April 12, 2007, Davis' attorneys filed a final appeal with the US Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari, a petition for the Court to review the case. On June 25, the petition was denied, and execution was set for July 17, 2007.

Motivated by mounting public discussion and appeals by noted celebrities, lawyers for Davis filed an extraordinary motion for a new trial on July 9, stating this time that there was substantial evidence that another man (Redd Coles) shot and killed MacPhail. Tonya Johnson, a witness in the case, stated that she saw another (unidentified) man dump the guns (that were never recovered) after the shooting. She said she didn't say that earlier because she feared the man she believed to be the actual shooter. As a witness at the trial, she was available for examination and cross examination then, so her later testimony is at very least suspect. On July 13 Judge Penny Haas Freesemann of the Eastern Judicial Circuit of Georgia, considering the evidence so far presented, rejected Davis' appeal and refused a stay of execution.

On July 16, the Board of Pardons and Paroles suspended execution of Davis' sentence for 90 days to allow appeals and consideration of the Board of the post trial developments. In most states, the governor has the prerogative of granting clemency by reducing the sentence, or of overturning it completely and letting the convict go free. This authority is a last-ditch protection against judicial or legislative impropriety, and represents one of the checks and balances between the three branches of government. In Georgia, this authority is exercised by the Board of Pardons and Paroles.

On August 3, the Georgia Supreme Court agreed to hear an appeal for a new trial. This made a second clemency hearing, scheduled for August 6, unnecessary. On November 13, the Georgia Supreme Court heard Davis' request for a new trial. On March 17, 2008, having considered the new potential testimony, it rejected Davis' contention that witness recantations should allow a new trial. They rejected a second request in April.

On September 3, 2008, execution of Davis' sentence was set for September 23. The Board of Pardons and Paroles rejected a clemency request on September 12:

Less than 2 hours before Davis was scheduled to be put to death on September 23, the US Supreme Court granted Davis a stay of execution to review his case, considered it, and rejected his request on October 11th. The new execution date was set for October 27th. The 11th US Circuit Court of Appeals granted a stay on October 24th and heard evidence for a new trial on December 9th.

The 11th Circuit Court rejected Davis' appeal (again) in April of 2009. This decision was again appealed to the US Supreme Court, on May 19th. On August 17th, the US Supreme Court ruled that the US District Court for the Southern District of Georgia must "receive testimony and make findings of fact as to whether evidence that could not have been obtained at the time of trial clearly establishes [Davis'] innocence." Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, wrote that "[t]he substantial risk of putting an innocent man to death clearly provides an adequate justification for holding an evidentiary hearing." Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas dissented, stating that a new hearing would be "a fool's errand" because Davis' claim of innocence was "a sure loser." In preparation for the new evidentiary hearing before the 11th Circuit Court, Davis' lawyers began in January 2010 to seek police files in the case, for evidence that the police might have kept secret at trial. Attorneys for the state of Georgia, on the other hand, questioned the propriety of the witness recantations.

In response to the August 17, 2009, US Supreme Court ruling to hear new evidence, Judge William T. Moore, Jr. of the US District Court for the Southern District of Georgia, held a two-day hearing in June of 2010. Judge Moore allowed evidence that normally would not have been allowed at trial, possibly to resolve public doubts about the validity of Davis' conviction.

The problem that Judge Moore was presented was this: Davis had been convicted 21 years previously by a jury of his peers, based on overwhelming testimony about then recent events. The jury concluded that his guilt was such that he deserved the death penalty. All the witnesses' memories were fresh, and their testimonies were essentially all in agreement. Both prosecution and defense had the opportunity to cross examine every one of them, of which 34 were for the prosecution and only six (including Davis himself) testified for the defense. Appellate courts all the way to the US Supreme Court had found not a single substantive error in the application of the law to this case. By US and Georgia law, nothing stood in the way of putting Davis to death.

On the other hand, the US Supreme Court had directed Judge Moore to examine the "new" evidence that Davis' lawyers claimed would prove his innocence. But there wasn't any new evidence. Every single one of the witnesses who claimed to have lied on the witness stand were cross examined at that time by the defense, whose job it was to cast doubt on their credibility then. Either the witnesses were lying then, or they were lying now, and nobody knew what weight, if any, had been, or should have been, given by the jury to their testimony. Davis himself did not present any new evidence of his innocence, only excuses for why he was originally convicted.

Worse, his whole argument rested on the implication of Redd Coles as the murderer, which could certainly have been presented at the trial. Obviously, somebody shot Michael Cooper. MacPhail definitely died from two gunshot wounds that were not self-inflicted. Davis, already lawfully convicted, was innocent only if Coles was guilty, and vice versa. The only implication of Coles were the statements of three witnesses, self-admitted perjurers all, that Coles had told them he killed MacPhail. They didn't even claim that they had seen him do that, only that he claimed that he did. (Even if he had done that, he could have been joking about it, or just plain wrong. MacPhail died from two gunshot wounds. Davis' attorneys would have had to prove that only wounds inflicted by Coles actually killed him.) Somebody definitely killed MacPhail, and Davis was the only person who had been found guilty of doing so.

Hearsay, the claim that somebody not available for questioning said something, is generally so suspect that it is not even admissible in court. Coles had not been indicted, much less convicted of shooting either Cooper or MacPhail, while Davis' conviction was upheld all the way to the US Supreme Court (four times). To be successful, Davis' lawyers would have to get Coles to admit under oath, and maintain under cross examination, that he himself, not Davis, had murdered MacPail. They would also have had to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the shots Coles would have had to have sworn that he fired were actually the ones that killed MacPhail. Essentially, they would have had to prove that MacPhail did not die because of whatever Davis did or failed to do.

Perhaps predictably, they didn't even call Coles! With over nine months to find and subpoena him, defense lawyers claimed that they had tried to find him the day before the hearing and couldn't. Judge Moore criticized their actions, saying that Coles was "one of the most critical witnesses to Davis' defense," and rejected the hearsay evidence as having no weight.

The prosecution, on the other hand, rebutted all the witness' claims that their original testimony was coerced and that there was no basis to believe that they were not coerced into changing their testimony since then. They pointed out that the testimony of at least five prosecution witnesses remained unchallenged. Current and former police officers and two lead prosecutors, testified that they had been very careful to indict "the right guy." Judge Moore in June concluded that Davis' lawyers had failed to demonstrate "clear and convincing evidence" of his innocence, calling their arguments "smoke and mirrors." His summary of the evidence and testimony in the case was 174 pages long!

In July, Davis' lawyers filed a motion asking Judge Moore to reconsider his decision to exclude testimony from an alleged witness to Coles' confession, but in August 2010, Moore stood by his initial decision. He maintained that in not calling Coles, Davis' lawyers were seeking to implicate Coles without allowing any chance of rebuttal. In November 2010, the federal appeals panel dismissed an appeal on the case, without ruling on its merits. They stated that Davis should appeal the case directly to the US Supreme Court "because he had exhausted his other avenues of relief."

In January, 2011, Davis' legal team filed a fifth petition with the United States Supreme Court, alleging that the 11th Circuit panel had "evinced a clear hostility" during his August 2010 appeal, and again asking for a new trial. The petition was rejected without comment by the Supreme Court March 28, 2011, allowing a new execution date.

On September 6, a new execution order was signed by Judge Freesemann, this time sitting on the Chatham County Superior Court, for between September 21 and 28. The Georgia Department of Correction set the date of execution for September 21.

On September 15, 600,000 petitions were delivered to the Board of Pardons and Paroles, which denied Davis clemency on September 20. Davis had proposed to take a lie detector test, but only if the State of Georgia agreed beforehand to spare his life if he passed it. The State declined the offer.

Davis' supporters delivered 240,000 signatures to Chatham County District Attorney Larry Chisolm's door on September 21, asking him to vacate the order authorizing the execution of Davis' death sentence. On the same day, Davis' attorneys filed a request for a stay of execution to the Georgia Supreme Court and the US Supreme Court, both of which denied his request. He was put to death at 10:58 PM, September 21, 2011, the same day as Lawrence Brewer, and pronounced dead ten minutes later.

Amid all the discussion and claims and emotion, the restriction of Gregg v. Georgia, seems to have been overlooked. Although the conviction of murder had been upheld five times all the way to the US Supreme Court, Davis could have avoided being put to death if he had demonstrated, a "character and record...to allow a lesser sentence." In essence, out of the 840,000 signed petitions, the defense lawyers and all of their witnesses, nobody, absolutely nobody, including Jimmy Carter, Al Sharpton, Pope Benedict, Archbishop Tutu, Bob Barr, Bill Sessions, or Davis himself, could come up with a single good reason to keep him, personally, alive - not one! The case is widely described as "controversial," but it wasn't controversial to the jurors, every last one of whom agreed that Davis should die for having murdered MacPhail.

I have to admit, I don't know who killed MacPhail or Byrd. I don't even know positively that they're dead, or that they even existed in the first place. As far as I can see, the people whose job it was to decide those things did their jobs at least as well as I've ever done any of mine. I'm OK with that! They might have to decide on my guilt or innocence some day, too.

There is usually no good reason for accepting recanted testimony, and two very good arguments against it. The witness is obviously not very careful about telling the truth in any case. At very least, he is the worst kind of liar. To be useful in court, testimony must be sworn or affirmed, and anyone who swears to one allegation and then to the opposite at another time is automatically guilty of perjury, which is itself a crime. Who is going to commit a crime right in front of a judge and jury? And even if he does, which of the two stories does one believe?

The second argument against recanted testimony is that it potentially subjects every trial witness to harassment and intimidation forever after the trial. If the convict believes he can be exonerated eventually by recanted testimony, there is strong incentive for him to arrange for that to happen. For these reasons, courts are extremely unlikely to admit recanted testimony at all. No matter how emotionally compelling, it rarely creates rational doubt.

The State was well within its rights to reject the offer of the lie detector test, which is notoriously unreliable, and would have proved nothing. Davis would have lost nothing if he failed the test, while passing it would have generated another unwarranted, and totally irrelevant, appearance of innocence that was already obfuscating the truth.

The fact that people who knew about the case only from news coverage had "too much doubt" about Davis' guilt does not imply that the jury did, and their opinions are the only ones that count. One juror was reported to have claimed that "if she knew then what she knows now she would not have voted the way she did," but that is precisely why the judge is there, to make sure that whatever doubts the jury might have are based only on what is presented in court and taken into consideration then. Jurors are carefully instructed to base their decisions only on the evidence presented, and in many jurisdictions are required to assert that they did that when rendering a verdict. Where there is reasonable likelihood for undue influence, the jury can be sequestered, so that they have no contact with potentially contaminating expressions of opinion at all. Jurors can also simply change their minds, but it is their unanimous decision at the trial, in open court, that governs the finding.

Of course, the appeals process is intended precisely to examine each and every objection to see it if is relevant, according to law. Davis had five of them, all the way to the US Supreme Court. He lost every single one!

One of the points raised by the media was that no weapon was found. This, too, is irrelevant. MacPhail died of gunshot wounds, so somebody obviously shot him. Coles claimed that he had a gun, but had given it away to someone else earlier. Davis was known to have possessed one, because he had been previously convicted (after pleading guilty) of carrying a concealed weapon without a permit. The introduction into evidence of a weapon, especially the one used to fire the bullets that killed MacPhail, may or may not have been useful to one side or the other, but the jury decided it was not necessary for a conviction. It's their call.

Similarly, the media concern about lack of DNA evidence is meaningless. Davis was convicted of shooting MacPhail to death, not raping him. It is difficult to understand what the term "DNA evidence" might mean, if anything, in this case.

There seemed to be widespread comparison with the Casey Anthony case, with the conclusion that Casey Anthony was found not guilty because she was white, while Davis was found guilty because he was black. This is surely a case of people looking for facts to support their biased conclusions, however dubiously. The difference between the Casey Anthony and Troy Davis trials is about the same as that between a hippopotamus and a lily. In addition, Casey Anthony was found guilty of lying to investigators. Besides, what about Lawrence Brewer?

In an interview with Diane Sawyer on ABC News, commentator Dan Abrams pointed out that 64% of Americans polled favor the death penalty, up from 50% in 1971, while only 29% positively oppose it (7% have no strong opinion either way). Out of about 15,000 lawful death sentence executions in the history of the United States, more than 50% have been white. At the present time, about 40% of the convicts awaiting death in the US are white, and 42% are black, while the black population of the US is less than 13%. Since 1976, when many states reinstituted the death penalty after it was suspended by Furman v. Georgia, 77% of death penalty victims have been white and 15% have been black. The implication seemed by some to be that black murderers are more likely to be sentenced to death, especially if they kill a white person. The alternative explanation is that the proportion of white to black victims is roughly that of the population as a whole, while capital felony murderers are seven times more likely to be black criminals, for some reason, than white ones.

In McCleskey v. Kemp, the Supreme Court examined this issue with respect to a similar case in Davis' home state of Georgia. In 1987, the US Supreme Court upheld the death penalty for convicted black armed robber and murderer Warren McCleskey, who also had shot a white police officer to death while the victim was in the performance of his duty. McCleskey's lawyers showed that the number of black people who are put to death for murdering whites is vastly greater than their proportion of the US population as a whole and that of whites who murder blacks. What they also demonstrated is that black people are more likely to murder white people than the other way around. The "racially disproportionate impact" in the Georgia death penalty indicated by the comprehensive scientific study was determined not to be enough to overturn the guilty verdict in this particular case without showing a "racially discriminatory purpose." Basically, the colors of the criminals are not a factor in their guilt, no matter how many of them there are. Are black criminals more likely to murder somebody than white ones? McCleskey's own statistics say yes. Should they be denied the same penalty that white folks get for the same crime because of their color? The Supreme Court says that the Fourteenth Amendment says no.

A more recent case involved a failed Supreme Court appeal from condemned murderer Kristopher Love. He claimed discrimination by juror Zachary Niesman, who replied, "No" to the jury questionnaire: "Do you sometimes personally harbor bias against members of certain races or ethnic groups." Niesman was then asked, "Do you believe that some races and/or ethnic groups tend to be more violent than others." Niesman replied, "Yes, statistics show more violent crimes are committed by certain races. I believe in statistics." The US Supreme Court decided 6 to 3, without explanation, that this answer did not constitute disqualifying racial bias against Love, or alter the "guilty" finding or the resulting death sentence.

I was struck by the argument that Davis' sentence should be commuted to that of life in prison without possibility of parole because he might not have been guilty. I don't follow this reasoning at all. If he wasn't guilty, he should have been set free! I actually said this in an email to Georgia Governor Nathan Deal. The idea that we should punish Mr. Davis with life in prison because he might not be guilty sounds much less to me like "justice for Troy Davis" (not to mention mercy) than executing the sentence imposed by the jury because everyone whose opinion counts thinks that he is.

Actually, I don't like that position, either, but that is the law. I discuss this at length elsewhere, so I won't do it here. No doubt many who were reported to have "supported" Davis, such as, for example, Pope Benedict, were actually opposed to putting anyone, even Saddam Hussein, Jeffrey Dahmer or Timothy McVeigh, (not to mention Lawrence Brewer) to death for their crimes. In the United States, we have established methods of dealing with people accused of murder. However defective these laws may be, they are the law of the land and they were all observed in this case. That's the way we do things here. People who don't like that should either use what political power they have or can acquire to change the law more to their liking, or live elsewhere.

Life itself involves implicit risks. People who are unwilling to take them shouldn't do that. Flying is the safest form of travel by far, yet every year people die in airplane crashes that they could have avoided easily by not flying. Over 34,000 people die in traffic deaths every year simply by being where the traffic is. Recently, a dozen people in the US died just from eating cantaloupe. Every person who lives in the United States runs a small but finite risk of being put to death for a horrible crime that maybe, just maybe, he didn't commit. Unless the voters of Georgia repeal the death penalty in their state, they are all subject to its potential mistaken imposition. So far, they have been willing to live with that for the benefits it provides them positively of eliminating the social threat of the very worst of their dangerous felons - such as Troy Davis.

Troy Davis lived in Georgia, taking advantage of its blessings, benefits and opportunities, including personal protection from criminals previously put to death and free legal counsel, all his life. Given all the foregoing Georgia death penalty cases previously noted, Georgia has to rank as one of the foremost death penalty jurisdictions in the world - not a good place to live if you illegally carry a gun around and eventually murder somebody with it! There is no evidence whatever that Davis did anything at all to abolish the death penalty in Georgia or to establish mitigating factors that would have demonstrated that he personally should have been exempt from it. He should have stayed away from guns, violence, and bad companions. He should have spent his time productively at a job or in the armed forces to establish a "character and record...to be taken into account, to allow a lesser sentence." He should have reported the crime immediately instead of keeping quiet and suddenly driving to Atlanta for no apparent reason. Maybe he should have moved to West Virginia or Illinois, or even Mexico or some other country where they don't have a death penalty. If he wanted positively to avoid a death sentence, he shouldn't have lived in Georgia, or gotten involved in the beating of Larry Young.

He probably shouldn't have murdered that police officer, either.