|

|

Some time ago our beloved pastor, in announcing the beginning of Catholic School Week, explained that the difference between Catholic and public schools was that in the Catholic school, you could talk about Jesus.

Actually, you can talk as much as you want about Jesus, Mohammed, Moses, Lao Tse, Buddah, or any other religious subject in the public school as long as you don't disrupt the curriculum. The Supreme Court has ruled that students' First Amendment rights to free religious expression allow them to pray privately in schools, whether alone or in groups, to read Bibles or other religious literature, and to organize religious clubs. But because of the constitutional prohibition against government establishment of religion, schools and school employees are not permitted to endorse, organize or sponsor those activities. Put simply, public schools are agencies of the government; religious schools are not. For this reason, public schools are required by law equally to accommodate students of all religions, or no religion at all, without discrimination. It's called "freedom of religion." It's a good thing!

On the other hand, religious schools are agencies of the religions that sponsor them. You can't swing a dead cat in a Catholic school without hitting something having to do with God, or Jesus, or Mary, or the saints, or someone specially revered by the Catholic Church. The kiddies are told how, when, under what circumstances and to whom to pray. Religious schools generally actively discourage freedom of speech and religion, because the students are supposedly there to learn what to believe and say. That's why the churches pay for them and they can accept or reject anyone they want. Students of other faiths (or none at all) are accepted under certain circumstances if they agree to requirements of the school for student participation. These generally include public prayer, Scriptural study, and lessons in specific religious belief, history and practice.

This absurdly simple dichotomy between state and religious schools is so difficult for otherwise pious people to accept that I suspect that Dark Powers are at work against it. Consider the case of the Webster Parish, Louisiana, School District, a religious institution in everything but name, using taxpayer money to promote Evangelical Christianity.

A complaint filed by Christy Cole, the mother of Webster Parish School District student Kaylee Cole, alleges that the District has a longstanding custom, policy, and practice of promoting and inculcating their own particular religious beliefs. They do this by sponsoring religious activities and conveying religious messages to students, including broadcasting prayers daily over school speakers. She claims that official promotion of religion at Parish schools includes virtually all school events - sports games, pep rallies, assemblies, and graduation ceremonies. These typically include school-sponsored prayer, religious messages and/or proselytizing. It is further claimed that graduation ceremonies are frequently held in houses of worship, and at times they resemble religious rituals that include Bible verses and Evangelical Christian prayers. Kaylee and her sister, Ana Lopez-Cole, have allegedly been subjected to this unlawful indoctrination, and have been shamed, mocked, harassed and intimidated when they did not fully participate, since kindergarten. Ana Lopez-Cole has apparently graduated from the District school system, and so does not now appear to have standing with respect to this complaint. Not so Kaylee and her mother.

Ms. Cole and her daughter Kaylee have sought a declaratory judgment that the School District's policies and practices are unconstitutional. They have requested injunctive relief enjoining the School District and its agents from continuing their unlawful practices, and compensatory damages for the mental and emotional distress and discomfort the Cole family has suffered.

It appeared to me that the Coles had a pretty good case. The kind of behavior alleged is precisely that found unconstitutional in the decision of Santa Fe School District v Doe, which was handed down in 2000, the year Kaylee was born, so the District Superintendent and the various school principals can't use the excuse that they should not have known better. The Webster Parish School District, its faculty and Evangelical students appear clearly to have conveyed, with malice aforethought, the message that only Evangelicals are favored members of the political community, and that Kaylee and other Baptists (and others) are outsiders, not full members of it. That message is a bare-faced lie!

In interviews I saw on television with residents of Webster Parish, I was struck by their common expressions of utter confusion regarding unlawful religious indoctrination, and unwelcome proselytization of others, versus voluntary exercise of their own, personal religion. It's as if Evangelicals are unable individually to do anything religious unless they force everybody else to do it - their way. They don't see a distinction between voluntary and compulsory prayer in public schools. They strike me as ignorant, intolerant, holier-than-thou bigots. I wonder where they learned that.

Given this confusion among our non-Catholic brethren, and possibly some Catholics as well, I believe that members of the Catholic Church are obliged, with due respect for consistency if nothing else, to recognize and support the Constitution of the United States in the matter of religious freedom. In what follows, I intend to show that the official position of the Church and the decisions of the Supreme Court are in harmony with one another. At issue is the right of adherents to all faiths, Catholics included, to practice their religion, and the right of those who reject all religious faith to exercise their constitutional rights in that regard as well.

To summarize the Catholic Church's position, I refer to the Dignitatis Humanae, "On the Right of the Person and of Communities to Social and Civil Freedom in Matters Religious," promulgated by Pope Paul VI on December 7, 1965. Article 2 states:

"This Vatican Council declares that the human person has a right to religious freedom. This freedom means that all men are to be immune from coercion on the part of individuals or of social groups and of any human power, in such wise that no one is to be forced to act in a manner contrary to his own beliefs, whether privately or publicly, whether alone or in association with others, within due limits."

Article 6 continued,

"Since the common welfare of society consists in the entirety of those conditions of social life under which men enjoy the possibility of achieving their own perfection in a certain fullness of measure and also with some relative ease, it chiefly consists in the protection of the rights, and in the performance of the duties, of the human person. Therefore the care of the right to religious freedom devolves upon the whole citizenry, upon social groups, upon government, and upon the Church and other religious communities, in virtue of the duty of all toward the common welfare, and in the manner proper to each. The protection and promotion of the inviolable rights of man ranks among the essential duties of government. Therefore government is to assume the safeguard of the religious freedom of all its citizens, in an effective manner, by just laws and by other appropriate means."

This teaching is summarized in the First Amendment to what is surely among the most profound documents in the English language, the Constitution of the United States of America. The First Amendment, states simply, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

I should like to provide a Constitutional perspective of this issue.

In 1962 in Engel v. Vitale, the United States Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional for the state of New York to allow the recitation of prayer in their public schools. The prayer that had been read daily said: "Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers, and our country." This prayer was prescribed by the school, not by the students themselves, and obviously made no provision for the views of students who did not acknowledge the existence of "Almighty God" or their dependence upon Him, or who chose not to invoke blessings on themselves, their parents, their teachers, or their country. Since this prayer was recited in a school supported by Government funds and at which attendance was mandatory for school-aged children, the Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional.

This ruling, and other Supreme Court rulings which uphold the separation of church and state, have often been misunderstood. Many individuals and organizations, among them the Concerned Women for America (CWA) concluded that this ruling constituted a denial of religious expression to students. The source of their basic misunderstanding is failure to make a distinction between voluntary prayer in public schools, which is protected by the First Amendment, and any act of the Government to compel people to pray, which is prohibited. At issue is not a question of whether or not religious expression, in the form of prayer, is appropriate in the setting of a public school, but to what extent acts of public agencies, such as public schools, constitute a "law respecting an establishment of religion."

Many of these people support a constitutional amendment which, under the guise of "religious liberty" would make Christianity, and, more specifically, nondenominational Protestant Christianity, a state religion in the United States. They believe that, because compulsory prayer is prohibited, public schools are hostile to the rights of students to express religious opinions. However, the argument is not that any public school student anywhere in the Country has ever been denied the right to express his or her individual religious opinion by the school itself. Any such prohibition would be blatantly unconstitutional. The essence of the argument is that if the school somehow deprives students of their collective rights if it does not sponsor compulsory prayer.

This policy analysis is intended to give clarity to the current discussion of prayer in the public schools, in relation to the Free Exercise Clause of the United States Constitution. I am indebted to the Concerned Women for America (CWA) and their world wide web site at http://www.cwfa.org/policypapers/pp_prayer.html, since removed, from which most of this discussion is copied.

Twentieth century court decisions have placed the question of school prayer under the rubric of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The applicable part of that amendment reads:

* Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, [Establishment Clause] * or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; [Free Exercise Clause]

In order to understand the relationship between prayer as religious expression and prayer as an aspect of public education, it is helpful to understand:

1. The contextual history of the Constitution

2. The textual history of the First Amendment

3. The origin of the phrase "separation of church and state"

Each of these will be examined, and then the findings will be compared to the decisions of applicable Supreme Court cases.

When the Constitutional Convention first met in Philadelphia in 1787, the religious landscape of the states was varied. Most states gave official recognition to one established denomination. The state of Virginia, for example, recognized the Episcopal Church as representative of their state. Religious belief as an integral part of colonial life was not in question. Rather, religious problems that arose between states centered on the differences between states' established denominations. Thus, the ad hoc establishment of different state religions in the various states led to disunity among them.

The political landscape also bore marks of disunity. The Articles of Confederation had proved insufficient for governing, and the states were fighting over issues of taxation -- namely, who should pay the costs incurred by the Revolutionary War. As the Constitutional Convention convened, observers said that the idea of a Constitution, much less a nation, was fragile and quickly vanishing. Chaired by George Washington, this meeting of some of the original Founders was seen as a last attempt at unity.

During the Constitutional Convention, states squabbled and self-interest abounded, to the point that no progress was being made. It was then that an aged Ben Franklin stood to his feet and said:

"In the beginning of the contest with Britain, when we were sensible of danger, we had daily prayers in this room for Divine protection. Our prayers, Sir, were heard, and they were graciously answered. All of us who were engaged in the struggle must have observed frequent instances of a superintending providence in our favor. And have we now forgotten this powerful Friend? Or do we imagine we no longer need His assistance?

"I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth: 'that God governs in the affairs of man.' And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid?

...I therefore beg leave to move that, henceforth, prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven and its blessings on our deliberations be held in this assembly every morning before we proceed to business." 1

The 81-year-old Benjamin Franklin was not one of the more religiously-minded Founding Fathers -- he actually believed more in the rational views of the French Enlightenment -- yet he was willing to acknowledge the importance of prayer to the political aspirations of a nation, and was courageous enough to acknowledge this belief in public. Franklin's reference to "prayers in this room", "superintending providence," and that "a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice," clearly implies his belief in Protestant Christianity, as opposed to, say, Hinduism or Buddhism. Yet Franklin did not ask that Christian prayer be required or written into the proceedings, only that prayers "be held."

After the Constitution was written, the first ten amendments, known as the Bill of Rights, were added to ensure the maintenance of certain liberties not expressly stated in the Constitution. James Madison wrote the first amendment "religion clauses," and an earlier draft made his intentions clear:

"The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established..." 2

When the Antifederalists 3 saw the word "national" in Madison's earlier draft, they argued that his use of that word presupposed a powerful centralized government. That was not Madison's intention, so his wording was changed to the present construction. 4 Yet understanding the wording of Madison's first draft elucidates the fact that he intended to alleviate the fear that a national church, such as the Anglican Church in Great Britain, would rise to official preeminence.

The phrase "separation of church and state" is not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution because its drafters did not see a dichotomy between their religious beliefs and the document that constructed their Republic. The phrase "separation of church and state" came primarily from two sources, a letter Thomas Jefferson wrote to a group of ministers, and from the Supreme Court case, Everson v. Board of Education.

Thomas Jefferson wrote the famous phrase "separation of church and state" in a letter to the Committee of the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut. He was responding to the letter they had written, part of which said: 5

"...Our Sentiments are uniformly on the side of Religious Liberty -- That Religion is at all times and places a Matter between God and Individuals -- That no man ought to suffer in Name, person or effects on account of his religious Opinions -- That the legitimate Power of civil Government extends no further than to punish the man who works ill to his neighbor ..."

Jefferson's response to their letter was amicable. He said, 6

"...Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legislative powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should 'make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,' thus building a wall of separation between Church and State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties."

Jefferson's declaration of "a wall of separation between Church and State" expressed his opinion that the federal government did not have the authority to "prescribe even occasional performances of [religious] devotion." 7 He did not question the validity of religious belief, but constructed his "wall" to protect religious freedom of conscience from the potentiality of one federally recognized religion. His fears were not without precedent. In his Inaugural Address of the previous year, Jefferson had noted that America had "banished from our land that religious intolerance under which mankind so long bled and suffered." 8 Clearly, federal domination of religious freedom through one established church was the thing that Jefferson decried.

Today, Thomas Jefferson's "wall of separation" protects the rights of religious free expression by all students in public schools, regardless of whether or not their personal beliefs conform to those held by the majority of citizens, however large that majority.

The third article of the Northwest Ordinance, which Thomas Jefferson wrote, said: 9

"Religion, morality, and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged." In addition, when Jefferson founded the University of Virginia, the Pamphlet of University Regulations included two sections that read:

"No compulsory attendance on prayers or services. Each denomination to send a clergy to conduct daily prayers and Sunday service for two weeks." 10

Jefferson clearly recognized the danger that the public schools could overstep their authority by requiring students to participate in religious services, and sought to provide a means by which students could exercise their religious freedom, in concert with their own clergy, while attending a secular institution of higher learning which might otherwise deprive them of opportunities for religious expression. While he might be criticized for a certain amount of Christian chauvinism by his mention of "Sunday service," his intentions appear to have been on the side of religious freedom as he understood it.

The second notable mention of the phrase "separation of church and state" came in the 1947 Supreme Court case, Everson v. Board of Education. The plaintiff argued that the New Jersey law that reimbursed parents for the cost of bus transportation -- to public and religious schools -- violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The Supreme Court said that it did not. In effect, the Court ruled that the process of riding the bus to school, in itself, is not a religious act. In the majority opinion, Justice Black used language to set the stage for such rulings in the future. He wrote that the Establishment Clause created a "complete separation between the state and religion," thus affirming the concept expressed in Jefferson's letter written 10 years after the ratification of the First Amendment. Black's interpretation of Jefferson's words is entirely consistent with the text of the First Amendment, and set a precedent for future rulings.

Justice Black's opinion also outlined a number of principles (broken into sections for clarification) which have evolved into the Establishment Clause legal precedent: The "establishment of religion" clause means at least this:

(1) Neither a state or a government can set up a church.(2) Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another.

(3) Neither can force nor influence a person to go or to remain away from church against his will or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion.

(4) No person can be punished for entertaining or professing religious beliefs or disbeliefs, for church attendance or non-attendance.

Twentieth century courts, based predominately on Jefferson's letter and on the precedent created by Justice Black in Everson v. Board of Education, have argued that the Constitution separates all religious expression from the process of government. This is entirely in accord with both the textual history and the original intent of the author of these religion clauses, James Madison. While it simply ignores the assumption, based on Franklin's remarks, that the men who hammered out each section of the Constitution believed in the importance of daily prayer, it in no way prohibits the free expression of religious thought and worship by any citizen, whether a public figure or otherwise.

The Establishment Clause may have been misinterpreted to mean that any link to religion is "establishing" religion. One of the causes of this is a simple alteration of the wording in the First Amendment. The clause reads, "Congress shall make no law regarding an establishment of religion." It does not read, "Congress shall make no law regarding the establishment of religion," as it is often misquoted. If the article is read as "the," then it refers to establishment of all religion in general. If the article is "an," then it clearly refers to a specific religion or denomination, such as Protestant Christianity -- an interpretation backed up by historic records. Realizing that the amendment uses the word "an," helps elucidate the meaning of the Framers. So, rather than attempting to separate themselves personally from religious belief and expression, the Framers were trying to keep the government from establishing an "official" religion.

The 20th century cases that are pertinent to the issue of school prayer rely on those differences. Those after Everson have clearly been built upon its framework, as demonstrated through summaries of key cases: 11

* Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940) In this case, two Jehovah's Witness school children were suspended from school for refusing to salute the American flag. As a result of their expulsion, their father had to pay for them to enroll in a private school. Their parents claimed that the children's' due process rights (as opposed to their religious freedom) had been violated by the school district. An 8 to 1 Court Decision, the Court ruled that a school district's interest in creating national unity was sufficient to allow them to require students to salute the flag. The Court argued that students would not be pulled away from their faith by partaking in the pledge because their parents have a much greater influence than the school in their religious faiths. Since this case was about due process and not compulsory prayer, the court's decision is somewhat at odds with its later decisions regarding the latter concern.* West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943) The Court ruled 8 to 1 that a school district violated the rights of students by forcing them to salute the American flag. Here, the issue was one of religious freedom, as a group of Jehovah's Witnesses refused to salute the flag on the grounds that it was a graven image. The Court found that the flag salute forced students to declare a belief that could be contrary to their faiths and the state could not demonstrate that a clear and present danger would be created if the students were permitted to remain passive during the pledge.

* McCollum v. Board of Education (1948) By a 6 to 1 vote the Supreme Court agreed with Mrs. McCollum, an atheist mother, that it is a violation of the Establishment clause for Jewish, Catholic, or Protestant religious leaders to lead optional/voluntary religious instruction in public school buildings as a part of the course of instruction. Such a situation essentially compels students to engage in Jewish, Catholic, or Protestant religious practices.

* Engel v. Vitale (1962) has already been discussed. The Court ruled 7 to 1 that it was unconstitutional for a government agency like a school or government agents like public school employees to require students to recite prayers. Clearly, the prescription of prayer by a government agent, in this case the school, is "respecting an establishment of religion."

* Abington School District v. Schempp (1963). This case and Murray v. Curlett ("Murray" being the famous Madelene Murray O'Hair) were decided together because of the similarity of their constitutional questions. The Court ruled 8 to 1 against allowing the reciting of the Bible verses and the Lord's Prayer. Daily school-directed reading of the Protestant version of the Bible (King James Version) (without comment), and daily recitation of the Lord's Prayer, violates the Establishment Clause when performed in public schools. This is obviously compulsion to perform a religions act.

* Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) Closely associated with the issue of school prayer is that of religious proselytization. In Little Rock, Arkansas, a high school biology teacher found herself in a dilemma when she realized that her district had adopted a book containing evolution: she could either use the book and violate a criminal law, or refuse to use the book and risk disciplinary action from the school board. She choose to try and eliminate the dilemma by eliminating the law. She challenged the constitutionality of the Arkansas statute prohibiting the teaching of evolution in all schools, included universities. In Arkansas, no teacher was permitted "to teach the theory or doctrine that mankind ascended or descended from a lower order of animals," or "to adopt or use in any such institution a textbook that teaches" this theory. Although the Court agreed that control of the curriculum of the public schools was largely in the control of local officials, the Court nonetheless held that the motivation of the statute was a fundamentalist belief in the literal reading of the Book of Genesis, which is a religious belief, and that this motivation and result required the voiding of the law. The Court further ruled that the State may not tailor the education of students to the principles of any religious group. This is an absolute prohibition that may not be violated. The law was not neutral because it did not prevent all discussions of the origin of man.

* Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District (2005) Another attempt to teach religion by pretending that it is science became the subject of a direct challenge in the United States federal court system against a public school district that required the presentation of "intelligent design" as an "explanation of the origin of life." The plaintiffs, including Tammy Kitzmiller, parents of Dover Area high school students, successfully argued that intelligent design is a religious doctrine. The judge, noting that the defendants repeatedly lied under oath to obfuscate the facts of the case, found "that the secular purposes claimed by the Board amount to a pretext for the Board's real purpose, which was to promote religion in the public school classroom, in violation of the Establishment Clause" of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

* Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) On June 28th, 1971, the Court unanimously (7 to 0) determined that the direct government assistance to religious schools was unconstitutional. This decision created the three-part "Lemon test" for determining violations of the Establishment Clause. To avoid a violation, an activity must meet the following criteria:

1. have a secular purpose;

2. not advance or inhibit religion (in principle or primary effect);

3. not foster excessive entanglement between the government and religion.* Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972) On May 15th 1972 the Court ruled 6 to 1 that the compulsory education law in Wisconsin did indeed violate the Free Exercise Clause for Amish parents. Justice Burger wrote in his majority opinion that the Amish have a legitimate reason for removing their children from school prior to their attending high school. The qualities emphasized in higher education (self-distinction, competitiveness, scientific accomplishment, etc.) are contrary to Amish values. The Court first determined that the beliefs of the Amish were indeed religiously based and of great antiquity. Next, the Court rejected the State's arguments that the Free Exercise Clause extends no protection because the case involved "action" or "conduct" rather than belief, and because the regulation, neutral on its face, did not single out religion.

* Committee for Public Education v. Nyquist (1973) A New York law offered grants to non-public schools that served a large number of low-income students and tax deductions to parents who sent their children to them. The money was given for the maintenance of school facilities. The Court found all three sections of the New York legislation unconstitutional because it found that each of the three parts of the law had the primary effect of furthering religion. There was no way to ensure that the money is only used for maintaining secular facilities. The tuition reimbursement also aided religion because the State cannot limit the use of tuition funds to only secular purposes. In effect, the reimbursements acted as an incentive for parents to send their children to private schools. The tax-deduction program was unconstitutional for the same reasons as the low-income grant program.

* Wolman v. Walter (1977) The Court allowed Ohio to provide standardized tests, therapeutic and diagnostic services to non-public school children. However, the state was not permitted to offer educational materials or subsidize class field trips. The supplying of educational materials was found to be unconstitutional because it has the "primary effect of providing a direct and substantial advancement of the sectarian enterprise." The need for state surveillance to ensure that state funds were used only for secular subjects failed the "excessive entanglement" portion of the Lemon Test. The field trip provision is unconstitutional and differs from the busing permitted in Everson because the non-public school has greater control over the timing and frequency of the trips, and a religious teacher could impart a religious meaning to a field trip taken to a secular place. As a result, the funding of field trips must be treated as the giving of educational materials to private schools.

* Stone v. Graham (1980) The Court struck down a Kentucky law requiring public schools to post the Ten Commandments in each public school classroom in the state with a notice of "secular application". The requiring of religious symbols or teachings was found to be sufficient to demonstrate governmental endorsement of their message, regardless of who ultimately funds them. Even if the schools hope for the Ten Commandments to be viewed through a secular framework, their historical and religious basis makes them irrefutably religious.

(It is perhaps germane at this point to note that the law specifically required the posting of the Ten Commandments. It did not require (or in fact allow) the posting of something like the following, which might have been permissible, as they are reasonable standards for getting along in civilized society:

1. Don't worship things.

2. Don't curse, or swear falsely.

3. Take a day off from work at least once a week.

4. Respect your parents.

5. Don't kill each other.

6. Don't have babies you can't take care of.

7. Don't take each others' things.

8. Don't lie to each other.

9. Don't attempt to break up each others' marriages.

10. Don't desire to possess what you can't have.)* McLean v. Arkansas (1981) The Supreme Court found that an Arkansas law prohibiting the teaching of evolution was impermissible because it violates the Establishment Clause and prohibits the free exercise of religion. This decision is one of several which made it clear that creationism and creation-science, no matter how carefully dressed up, would continue to be regarded for what they are: religious doctrines. Thus, this avenue which fundamentalists attempted to use to sneak religious education into public schools has been closed down.

* Lynch v. Donnelly (1983) Petitioners brought a suit against the city of Pawtucket, Rhode Island claiming that a display owned and operated by the government and including religious scenes violated the Establishment Clause because it clearly sponsored religion. The Court ruled 5 to 4 that the city could continue to display a nativity scene as part of its Christmas display. The city's inclusion of the creche in its Christmas display had a legitimate secular purpose in recognizing "the historical origins of this traditional event long [celebrated] as a National Holiday," and that its primary effect was not to advance religion.

* Marsh v. Chambers (1983) By a 6 to 3 vote the Supreme Court permitted the practice of beginning the legislative session with a prayer given by a publicly funded chaplain. The Supreme Court ruled that they and Congress have traditionally begun their sessions with prayers, and individual states do not have to abide by more stringent First Amendment limits than the federal government. The "Establishment Clause does not always bar a state from regulating conduct simply because it harmonizes with religious concerns." The public payment of the chaplain is historically allowable because it was done by the Continental Congress years earlier. The pervasiveness of involving prayer with governmental activity without adverse effect has shown that there is no real threat from continuing the practice.

* Grand Rapids School District v. Ball (1985) Grand Rapids School District offered two programs conducted in leased private school classrooms: one taught during the regular school day by public school teachers and the other taught after regular school hours by part-time teachers. Both were found unconstitutional. Both programs, the Court held, had the effect of promoting religion in three distinct ways: the teachers might be influenced by the "pervasively sectarian nature" of the religious-school environment and might "subtly or overtly indoctrinate the students in particular religious tenets at public expense." Also, use of the parochial school classrooms "threatens to convey a message of state support for religion" through "the symbolic union of government and religion in one sectarian enterprise." Finally, "the programs in effect subsidize the religious functions of the parochial schools by taking over a substantial portion of their responsibility for teaching secular subjects."

* Aguilar v. Felton (1985) In a 5 to 4 Court Decision in 1985, the Court overturned New York City's program of paying the salaries of public employees who provided remedial assistance to low-income students in parochial school environments. The Court ruled that although it was true that the state's assistance to parochial schools did not have the primary effect of advancing religion, the closeness of interaction between state and church nevertheless had that result:

* Wallace v. Jaffree (1985) The Court found that an Alabama law requiring that each school day begin with a one minute period of "silent meditation or voluntary prayer" was unconstitutional because the intent of the legislature was deemed to be religious rather than secular. In effect, the government can require a student to be silent for other purposes, but it cannot require him or her to be silent for the purpose of praying. Interestingly, The Court characterized this legislative attempt to return prayer to the public schools as "quite different from merely protecting every student's right to engage in voluntary prayer during an appropriate moment of silence during the school day."

* Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) In a 7 to 2 Court Decision, the Court invalidated Louisiana's "Creationism Act" because it violated the Establishment Clause; Creationism, however camouflaged, is blatantly a Protestant Christian religious doctrine. The state tried to argue that the law was simply designed to promote academic freedom by ensuring that students would hear about more than one theory on the origins of life, but the Court correctly noted that teachers were permitted to present more than one such theory before the law. The actual purpose of the law, then, had to be to make sure that creationism was taught if anything at all was taught.

* Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School v. Grumet (1989) In 1989, the New York legislature drew new boundaries for a school district to accommodate the village of Kiryas Joel. This area was overwhelmingly occupied by people who practiced Satmar Hasidim, a particularly strict form of Judaism. In a 6 to 3 decision, the Court found that the boundary was unconstitutionally drawn to include only those people who lived in the area occupied by the members of the strict Jewish group and was thus a deliberate attempt to aid a particular religious group.

* Lee v. Weisman (1992) On June 24th 1992, the Court ruled in a 5 to 4 Court Decision that the graduation prayer during school graduation violated the Establishment Clause. Prayer cannot be offered by a private, non-governmental individual (in this case a Rabbi), at a public school graduation. Student rights were infringed upon, according to the Court, because the important nature of the event in effect compelled them to attend graduation. That, in effect, compelled students to bow their heads and be respectful during the prayer, which the court argued was a constitutional violation. This case is particularly interesting because it was brought by a Jewish student and her father, both of whom argued that the school had turned itself into a house of worship after the benediction by the Rabbi.

* Zobrest v. Catalina Foothills School District (1993) In 1993, the Court decided 5 to 4 to require a school district to offer a student in a private religious school the sign language interpreter he needed. The Court ruled that the sign language interpreter receiving the public funding did not add to the religious environment in which the student's parents chose to place their son..

* Agostini v. Felton (1997) On June 23rd, 1997, in a 5 to 4 Court Decision, the Court allowed public school teachers to tutor students in the private schools, even if the schools were primarily religious in nature. This is an interesting case because it arose out of a lower court decision which disallowed the public school teachers from teaching in private schools based on the previous Aguilar v. Felton decision. In Agnostini, the Supreme Court ruled that New York was forced to offer remedial help to students through "local educational agencies" and parochial school students did not need to attend public schools in order to be eligible for the assistance. The only students permitted to receive the federally funded assistance were those who resided in low income areas or who failed or were at risk of failing the state's student performance standards. In effect, tutoring a parochial student to help him meet state standards does not promote an establishment of religion.

* DiLoreto v. Downey USD (1999) The Supreme Court let stand, without comment, a 9th Circuit Court of Appeals decision that a school district was within its rights to discontinue a program of paid advertising signs on school grounds rather than accept a sign promoting the Ten Commandments.

* Santa Fe School District v. Doe (2000) With Justice Stephens writing the majority opinion, the Supreme Court ruled 6 to 3 that the District's policy permitting student-led, student-initiated prayer at football games violates the Establishment Clause.

This recent battle between the Supreme Court and those who equate the imposition of Protestant Christianity on public school students with religious freedom is especially significant because of the specificity of the issues involved. The Court held that the delivery of a message on school property, at school-sponsored events, over the school's public address system, by a speaker representing the student body, under the supervision of faculty, and following school policies which encourage public prayer could not justifiably be called private speech.

The Court also rejected the argument that the policy was different from the graduation prayer in Lee v. Weisman because it did not coerce students to participate in religious observances. The Court pointed out that one of the Establishment Clause's purposes is to remove debate over this kind of issue from governmental supervision or control. In the opinion of the Court, the election amounted to little more than an underhanded scheme to turn the school into a forum for religious debate. It also unjustifiably empowered a majority to subject students of minority views to constitutionally improper messages - something government agencies have no business doing.

The Court also noted that the policy did have an element of coercion in it. For example, some students, such as cheerleaders, members of the band, and the team members themselves, are indeed required to attend football games. There is also the tremendous social pressure experienced by many students to be involved in activities like football. According to the Court, schools should not force students to choose between attending these games or to "risk facing a personally offensive religious ritual." The decision on this point reads:

"School sponsorship of a religious message is impermissible because it sends the ancillary message to members of the audience who are nonadherents that they are outsiders, not full members of the political community, and an accompanying message to adherents that they are insiders, favored members of the political community."One difficult issue was the argument that the Court had no business issuing a ruling because, so far, no invocation has yet been delivered under the relevant policy. It was on this point that the dissent by Chief Justice Rhenquist, with Justice Scalia and Thomas focused strongly. They agreed that policy at issue could be applied in an unconstitutional manner, but that courts should wait and see what happened.

Also according to the dissent:

"...even more disturbing than its holding is the tone of the Court's opinion; it bristles with hostility to all things religious in public life. Neither the holding nor the tone of the opinion is faithful to the meaning of the Establishment Clause, when it is recalled that George Washington himself, at the request of the very Congress which passed the Bill of Rights, proclaimed a day of "public thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favors of Almighty God."It is not exactly clear why Justices Rhenquist, Scalia and Thomas found the ruling "hostile to all things religious in public life" although they clearly felt that the Court in this case had gone too far. Perhaps this case marks the limit at which the present Supreme Court will erect the "wall of separation."

Interestingly, this decision and Lee v. Weisman invalidate Mississippi Code of 1972, As Amended, Section. 37-13-4.1. Voluntary prayer at school-related student events, which states in part:

"On public school property, other public property or other property, invocations, benedictions or nonsectarian, nonproselytizing student-initiated voluntary prayer shall be permitted during compulsory or noncompulsory school-related student assemblies, student sporting events, graduation or commencement ceremonies and other school-related student events."This provision of state law is frequently invoked at Mississippi college and junior college sports events in which one of the faculty prays for his (godly) team to win and the other (ungodly) team to lose and enjoy good sportsmanship "in Jesus' Name, Amen," while all the students who don't "patriotically" remain silent and bow their heads in reverence for the name of the school's official Most Holy Savior are singled out as a bunch of no-good heathen troublemakers.

"The legislative intent and purpose for this section is" supposedly "to protect the freedom of speech guaranteed by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, to define for the citizens of Mississippi the rights and privileges that are accorded them on public school property, other public property or other property at school-related events; and to provide guidance to public school officials on the rights and requirements of law that they must apply." It is not at all obvious why the State of Mississippi needs to "protect the freedom of speech guaranteed by the First Amendment to the United States" rather than let the US Supreme Court do that. This law does exactly the opposite, which is why it's unconstitutional.

Mississippi has a long history of "protecting the rights guaranteed under the United States Constitution," by such methods as patriotically lynching "troublemakin'," "uppity" black people for not fully appreciating the way the Mississippi Klan was protecting their rights. Mississippians protected the civil rights of 48 soldiers and 30 U.S. Marshals who were injured in Jackson when James Meredith, to this day considered by many God-fearing Mississippians as an "uppity nigra," exercised his constitutional right to education by enrolling in the University of Mississippi.Notice that each of those cases focused on the Establishment Clause, and has nothing to do with the Free Exercise Clause. In none of these cases was it alleged that the rights of the students to pray or read the Bible were infringed. None of them involves an allegation that any student was prohibited from exercising his or her religion which, of course, would be unconstitutional.Mississippi was the last state reluctantly to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment on March 21, 1995. (It didn't complete the process by notifying the Office of the Federal Register of the fact until February, 2013.) The idea of Negroes having the same rights as people was especially hard for Mississippi legislators to accept. One of their latest atrocities is a Long Beach school board policy to compel students to "voluntarily" surrender all of their Fourth and Fifth Amendment rights for the dubious opportunity to participate in extracurricular activities so they can surrender their First Amendment rights there. There was even a Mississippi moron campaigning for the office of Governor whose platform includes "to bring back voluntary student-led school prayer to Mississippi schools and offer classes on Bible literacy." And he's a lawyer for God's sake! (Fortunately, he lost. Mississippi voters, Republican ones, anyway, are not as dumb as Mississippi politicians like to believe, which is a pretty low bar anyway!)

This is perhaps the most important point of this discussion. No plaintiff has ever argued before the Supreme Court that he personally has been prohibited from praying in a public school. All court cases involving school prayer have arisen out of a situation in which an individual or a group of individuals have been, or was in danger of being, required by a state-supported institution to conform to religious practices of others.

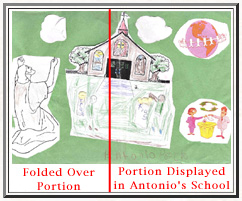

One student, Antonio Peck, drew a picture of a robed figure, that appeared to be Jesus, along with several religious phrases. His mother allegedly helped, but little Antonio was alleged to have claimed something to the effect that "only Jesus could save the environment." Ms. Weichert took the poster to Principal Robert Creme who told her to instruct Antonio to create another poster. Ms. Weichert then informed Antonio's mother that the poster could not be displayed and he would have to create a second one because (1) the poster contained religious content; and (2) it did not reflect what Antonio had learned during the section on the environment.

Little

Antonio's parents filed suit on his behalf in federal district court. They claimed essentially that (1) the school officials' censorship of Antonio's poster violated his free speech rights and to freely exercise his religion, and, (2) that the school's actions constituted "respecting an establishment of religion." The Baldwinsville Central School District argued that it's actions did not violate Antonio's rights because: (1) the first poster didn't fulfill the assignment, (2) the second poster showed evidence that it was more Antonio's mother's work than his, and (3) it could have given other parents the impression the school district was teaching religion. Federal District Judge Norman A. Mordue ruled against the Pecks and in favor of the Baldwinsville Central School District, summarily dismissing the case in February, 2000.

Antonio's parents appealed, and the 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals remanded the case back to Judge Mordue, ruling essentially that he had not considered all the facts in the case. Judge Mordue responded by dismissing the action again in August of 2004.

On a second appeal, the Second Circuit Court vacated the district court's decision on the free speech claim (but not the "establishment" claim, which it upheld) and remanded the case back to Judge Mordue. In effect, it said that Judge Mordue was correct that the school district did not, in this case, establish a religion, but that there was reason to believe that it had restricted little Antonio's right to exercise his religion, which Judge Mordue originally had denied. It also ruled that the Pecks could sue the Baldwinsville Central School District because there was evidence that Antonio's poster was censored because it expressed a religious viewpoint, which is blatantly unconstitutional. Both Ms. Weichart and Mr. Creme testified that they would have taken similar actions had the poster contained any other material not taught in the environmental awareness curriculum, but Ms. Weichart admitted that had Peck displayed secular images on his poster, such as a specific endangered species or the Sierra Club logo, she would not have automatically censored the poster because, she said, those images hold no religious significance. In essence, if a student had created a poster that contained non-religious images that had not been discussed in class, they would have treated the matter differently than they did with Antonio's religious expression.

The appellate court found that the school seemed "particularly disposed to censor Antonio's poster because of its religious imagery," while the school would "not necessarily" have gone down a similar path had Little Antonio submitted secular images that were just as non-responsive to Ms. Weichert's assignment.

In light of this guidance, Judge Mordue cited the precedent set in a 1984 Supreme Court decision in Hazelwood School District v. Kulhmeier. In that case the Court ruled that a school has a "legitimate pedagogical concern" in promoting student viewpoints in school publications, and therefore viewpoints in such publications have a lower level of First Amendment protection than if the school were not involved. Judge Mordue noted (1) "Since the intent of the poster assignment was to prompt the student to demonstrate what he had learned from the environmental lesson, it was reasonable for the educators in this case to be concerned that a parent viewing Antonio's poster might think he had learned about Jesus in class," and (2) the school did not violate Antonio's right to religious expression because, even when prompted, he did not discuss the figure of Jesus in the second poster, or how it might relate to the environment, at all.

In response to the allegation that the school would not have censured a Sierra Club logo, a picture of Smokey the Bear, a manatee or one of the New York Mets, Judge Mordue found that there was no evidence to support such a conclusion from such hypothetical situations.

This case has been to the US Supreme Court (which refused to hear it) and is back again. Judge Mordue has been steadfast in his decision that the school was within its rights, but the latest appeal involved a dismissal by the US Court of appeals on grounds that the Pecks have no further standing basically because Antonio is now in high school. His claim is basically that, since he is still a student within the school system, he is still a victim of the system's religious persecution. This time, hd did not ask for damages (taxpayers' money). The case was dismissed by Judge Mordue on order of the appellate court on the grounds that he now has no standing because, having declined to press his claim for damages, he failed to show that whatever the Baldwinsville Central School did in the past, or is doing now, is either illegal or is reasonably likely to harm him in the future.

Little Antonio has since graduated from Baldwinsville High School, removing him from the potential for future civil rights violations by the Baldwinsville School System. You can see some of his varsity football photos here. Hopefully, we have heard the last of this, but I doubt it.

While the Founding Fathers encouraged prayer during the Constitutional Convention and in ordinances governing education, the Supreme Court has repeatedly been called upon to prevent compulsory prayer. Perhaps Justice Sandra Day O'Connor most precisely defined the continuing position of the Court in Lynch v. Donnelly:

The most prevalent argument of such individuals is that by not respecting Protestant Christianity as a national religion, the government somehow prohibits Protestant Christians from practicing their religion, which includes, among other things, denying the civil rights of everyone who doesn't believe as they do. In fact, the First Amendment mandates that the government has a responsibility to be neutral, regardless of whether or not any child is offended by the religious speech, or lack thereof, of another. However, these people maintain that the government cannot be neutral. They maintain that elimination of compulsory Protestant Christian religious expression, allegedly to protect the civil rights of the atheist, will offend the child who believes in God and, furthermore, that such offense somehow deprives him of the right to practice whatever religion he believes in. So, they say, the schools must choose between either forcing every child to practice their particular brand of religion or prohibiting any child from doing so.

They do not make the same argument about wearing socks or eating pizza at lunch. I don't know why! What they are essentially saying is that their religion requires their government to force everyone else to conform to their beliefs, and if their government doesn't do that, it is infringing on their religious freedom. The only place they've made any headway with this argument is in Mississippi, but Mississippi ranks dead last in the educational level of its citizens. Just look at their reaction to hurricanes!

Neither one of these options is permitted by the First Amendment. Since Engel v. Vitale, these people have seen the refusal of the schools to make such a choice as upholding the rights of what they claim are a small, non-religious minority of atheists. They point out that atheists comprise only 3 percent of the population.

12 and that, by contrast, 94 percent of respondents to that same survey professed a religious faith, and 84 percent said that they agreed with the statement that "Religion is very important" in their lives.

13 They seem to regard these statistics as somehow justifying the establishment of a state-sponsored church which embraces most, if not all, of the principles peculiar only to Protestant Christianity. These proponents of state-supported religion claim that if free religious expression in the form of Protestant Christian prayer to a Protestant Christian God is not required, school officials are, at the very least, teaching children that public acknowledgment of God is not as important as the things that the schools can require. While this may or may not be true, it is totally irrelevant to the discussion, for the First Amendment prohibits any action by the state which does not allow free religious expression in the form of prayer. Any student in any public institution may pray any time in any way to anybody, as long as he does not infringe upon the civil rights of his teacher or his fellow students. The First Amendment guarantees him that right.

Of course, public schools can allow discussion, and even education about religion just as they can about sex, or any other subject, for that matter, as long as they stick to the facts. The public school can (and, in the case of several state universities does) have an open discussion about God, angels, Satan, and any other religious topic, pointing out that this religion preaches this and that religious group believes that, without embracing any specific belief as the one officially sanctioned by the state. But as soon as they say that one religion is preferable to another, or that it is morally acceptable to do or not do something, they are "respecting an establishment of religion" which is prohibited by the First Amendment. The courts have consistently ruled that public schools can (and must) allow free religious expression without embracing any particular religious thought.

There is a simple test that can be used to determine if a specific public school practice violates the Constitution. Substitute the term "Satan" for "God" and "damn" for "bless" everywhere it appears. If the resulting text is objectionable to Protestant Christians, the original is almost certainly unconstitutional!

Part of the reason that many Protestant Christians confuse compulsory prayer with free religious expression can be traced to the Catholic school system. The establishment of Catholic schools in the nineteenth century arose from a recognition by American Catholics that the First Amendment did not permit the teaching of their religion in public schools. Concerned that such a situation would result in their children not learning the tenets of their faith, the American Catholic bishops, meeting in Baltimore in 1852, took the bold step of establishing a Catholic school in every parish, in which the teachers would be paid from the parochial funds. Later councils in Baltimore more specifically defined the roles of these schools and developed a catechism of the elements of Catholic doctrine which were to be taught in them.

Since the establishment of Catholic schools, many Protestants have had similar misgivings about sending their children to schools which do not teach religion, and have established their own religious schools in which religion is taught and religious participation is required. Their right to do this is guaranteed by the First Amendment.

The establishment of a separate Catholic school system, in which the teaching of religion was the main reason for its existence, appeared to many Protestants to justify the teaching of Protestant Christianity in the public schools as a defense. But the public schools are not Protestant schools any more than they are Jewish or Mormon or Muslim or Hindu or Shinto or Satanist or atheist. They are public and non-sectarian, offering every citizen, Catholics and atheists included, the opportunity to receive an education at the expense of the state without constraining them to acknowledge or practice any religion at all if they freely choose not to do so.

An argument used sometimes seen as being against compulsory religious expression is that prayer "polarizes citizens around a religious axis."

14 Yet the First Amendment was written to avoid the squabbles that might result between denominations. Supposedly, the idea of not allowing prayer has done more to polarize citizens than almost any other political issue in American history,

15 in spite of the fact that this idea is precisely the opposite of all the court rulings on the subject. This polarization, of course, is caused specifically by those who choose to dispute what has been repeatedly asserted as the Law of the Land, not the Law itself. While some Protestant Christians maintain that compulsory prayer in public schools would put decision-making back in the hands of parents and local school boards, where it once rested, what they are actually talking about is requiring public school students to conform to the Protestant Christian religious preferences and practices of Protestant Christian parents and Protestant Christian school boards, such as the Webster Parish School District. The idea that local boards could set guidelines that would allow students who object to all prayer or some prayers to opt out ignores the very serious issue of what these children would do while their Protestant Christian fellows were practicing their state-sponsored religion, or how they would be protected from the potentially adverse social reaction of their Protestant Christian fellow students to such non-participation, such as that suffered by Kaylee Cole. Historically, social reaction to religious non-participation has even included the "heretics" being tortured to death in the name of religion!

The argument that this is the same as conservative Protestant students having opted out of sex education classes ignores the fact that freedom from being forced to practice religion is guaranteed by the First Amendment, and freedom from sex education is not. The rights of the minority are not upheld by subjecting them to the biting scorn of their fellow children because they are "different." These rights cannot be held hostage to the supposed rights of the majority. It is difficult to imagine what protection such hostage-taking would give to local school boards under the constitutional "time/place/manner" restrictions which apply equally to religious and non-religious speech that they do not have now.

16 However, whether establishment of a state-sponsored religion would benefit local school boards is beside the point. It is simply not permitted by the Constitution - period!

It may be that establishment of a state religion under the misleading guise of "a restoration of free expression," and the proselytizing of this religion in local public schools would unite, not polarize, citizens. However, the very idea of state-sponsored unification of ideas at the expense of the rights of the minority is totalitarianism, not "free expression," and is absolutely repugnant to the Constitution.

There is an additional danger which is mentioned rarely, if at all, in arguments for legislation permitting compulsory prayer in public schools. Authority to "allow" students to pray at certain times implies the authority to prohibit prayer at other times. As the First Amendment stands, it defends the right of a student to pray at any time if his religion (such as Islam) requires it. To assign one minute a day for silent or public prayer is to assert the right to deny the student the right to pray at any of the other 359 minutes or so of the school day. Far from a "restoration of free expression," such authority would severely limit the rights each American now enjoys to pray at times and in a manner which are a matter between him and his God, and make the state the arbiter of when, if perhaps not how anyone could pray. When the school starts "defining rights," extremely bad things happen, as in the Long Beach, Mississippi public schools.

The Constitution does not overtly mention God, but it does imply dependence upon a Creator through its last words, called the Subscription Clause. It says:

17

An interesting case, Peck v. Baldwinsville Central School District, arose in 1999 which possibly addressed the assertion that a public school denied a student his right to express his religious views. The case involved a homework assignment to students in Susan Weichert's kindergarten class at Catherine McNamara Elementary School in Baldwinsville, New York. The pupils were instructed to create posters showing what they learned about the environment. Ms. Weichert sent detailed instructions home informing parents that the content of the posters should reflect what the students had learned about the environment in class.

Antonio's second poster still contained the robed figure, but it also contained a depiction of people picking up trash and recycling next to a church. Principal Creme instructed Ms. Weichert to hang the second poster at the assembly but to fold the rest of the poster over the portion depicting the robed figure. However, Antonio was allowed to present the poster to class without any alterations. During the presentation he made no references to religion or God.

Antonio's second poster still contained the robed figure, but it also contained a depiction of people picking up trash and recycling next to a church. Principal Creme instructed Ms. Weichert to hang the second poster at the assembly but to fold the rest of the poster over the portion depicting the robed figure. However, Antonio was allowed to present the poster to class without any alterations. During the presentation he made no references to religion or God.

"The endorsement test does not preclude government from acknowledging religion or from taking religion into account in making law and policy. It does preclude government from conveying or attempting to convey a message that religion or a particular religious belief is favored or preferred. Such an endorsement infringes the religious liberty of the nonadherent, for [w]hen the power, prestige and financial support of government is placed behind a particular religious belief, the indirect coercive pressure upon religious minorities to conform to the prevailing officially approved religion is plain."

Some legal scholars and special interest groups have built upon those precedents, in an attempt to demonstrate that the Court has taken a stance against the Free Exercise Clause.

Done in convention, by the unanimous consent of the states present, the Seventeenth day of September, in the Year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and Eighty-Seven, and of the independence of the United States of America the twelfth. In witness whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names.

The fact that the Founding Fathers recognized the Constitution as written in the 12th year of independence, shows the Declaration of Independence to be America's founding document. The Declaration clearly acknowledges the Creator God.

18 However, while the Constitution is the very root of all United States Law, the Declaration of Independence is in fact a seditious document which has no force of law whatever anywhere.

The Founder's did not codify religion in the Constitution because Congress did not have the authority to govern religious thought. As James Madison so aptly put it, "Religion is the duty man owes to his Creator." 19 The members of Congress did not desire to create a theocratic form of government because they decided that religious belief is not under the jurisdiction of civil government.

The Constitution grants the free exercise of religion to every American, and that right should not and does not vanish at the doors of a public school. ANY public school student has the right, guaranteed by the school as agent of the state, to pray when, where and under what circumstances he chooses, as long as he does not disrupt his fellow students. 16

Just as government does not have the right to impose religion, government also does not have the authority to constrain free religious expression. The Declaration of Independence did not infringe upon the multiplicity of modes of worship in the states, yet it acknowledged God and unchangeable universal principles, such as inalienable rights.

That balance is still maintained today. Congress must not allow those Americans who, overwhelmingly or otherwise,20 favor a establishment of a state religion to create such a religion as the only means by which they feel comfortable in publicly expressing their individual beliefs.

Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, writing the opinion for McCreary v. ACLU of Kentucky, may have said it best:

"It is true that the Framers lived at a time when our national religious diversity was neither as robust nor as well recognized as it is now. They may not have foreseen the variety of religions for which this Nation would eventually provide a home... We owe our First Amendment to a generation with a profound commitment to religion and a profound commitment to religious liberty -- visionaries who held their faith 'with enough confidence to believe that what should be rendered to God does not need to be decided and collected by Caesar.'"

- Sandra Day O'Connor, Associate Justice

of the U.S. Supreme Court,

McCreary v. ACLU of Kentucky, 2004

Regarding Cole v. Webster, freedom of religion is among our most sacred civil rights. Kaylee Cole and her sister have been denied those rights by the Evangelical Webster Parish School District during all of their formative years. In Kaylee's case, this denial has led her to reject the Baptist faith she once held dear. She has been grievously harmed!

On May 11, 2018, Chief Judge Maurice Hicks of the US District Court for the Western District of Louisiana signed a consent decree and order in which the Webster Parish School District essentially agreed to all the allegations of improper proselytization against it and to the remedies ordered by Judge Hicks. His order laid out in minute detail what the District and its emplyees were to cease doing, and the definitions of each of its terms to avoid any "misunderstanding" or dispute. He also ordered the District to provide copies of the order to all current and future school officials and to provide ACLU approved training to the same, by an attorney, about what "freedom of religion" means. In addition he ordered the establishment and maintenance of an anonymous complaint process, with no time limit and appropriate protection of the complaintant(s), to allow identification, termination and rectification of future wrongdoing by the District. The order was signed by Christy Cole on behalf of her daughter, Johnnye Henson, the School Board president, Johnny Rowland, the Superintendent, Denny Finley, the principal of Lakeside High School, and the attorneys involved. The School Board was ordered to pay the Coles' expenses and attorneys' fees and the nominal sum of one dollar, but left open the option of the Cole family seeking further compensatory damages. Judge Hicks retained jurisdiction in the matter just in case the Webster Parish School District still didn't "get it."

My limited experience with Evangelicals is that they tend to be resistant to any change of viewpoint, but are strongly influenced by acquisition or loss of money. Perhaps they will be more inclined to believe in, and adhere to, the Law of the Land if the Coles are awarded enough in compensatory damages from their school system completely to bankrupt Webster Parish. Personally, I hope so. This kind of bullying has to stop!

If any public school student desires prayer in public schools, all he has to do is exercise his Constitutional right to put it there. That other Christians have not individually done so is perhaps a reflection on a timidity of openly professing or practicing their faith unless they feel backed up by the majority. But in The United States of America, no one, not the Federal Government, nor the state, nor the school board, nor the parents, nor Evangelicals, nor the Roman Catholic Church, has the right to force it on the student as a condition of his receiving the public education to which all citizens have an equal, unqualified right.

Thank God!

PS: In the regular session of the Mississippi Legislature that began in January, 2023, State Representatives Jeffrey Hulum, Otis Anthony, Bryant Clark, Alyce Clarke, Ronny Crudup Jr., Stephanie Foster, Debra Gibbs, Greg Haney, Hester Jackson-McCray, Gene Newman, Randell Patterson, Rickey Thompson and Kenneth Walker Submitted House Bill 488, a "trigger bill" that, if passed by the Mississippi senate and signed by the Governor, would update Mississippi law to: "...Require local school boards to designate a period of reflection at the beginning of each school day to provide for student-initiated prayer on a voluntary basis..." if the Mississippi Attorney General determines that the United States Supreme Court has overturned Engel v. Vitale. One has to wonder what would happen if one of the "student initiators" chose to begin his "voluntary prayer" with Bismallah elh rachman elh raheem or Shema Yisraeil, Adonai Eloheinu, Adonai echad! It seems that this would certainly invoke the Lemon Test. I note that HB 488 does not reference Sante Fe or Lemon, on which Sante Fe was based, which may make HB 488 difficult to enforce if these two decisions still stand.

Overturning Engel is not likely, as a number of subsequent findings were based on it, as noted above. It is therefore pretty well settled law. However, Representatives Hulum et. al. appear to have hopes that the same thing that was recently done with Roe v. Wade can be done similarly with Engel by the same or future turncoat Justices. That doesn't really have to happen to trigger the law, though. The sponsors have cleverly provided a possibility of unilaterally doing that if the Mississippi Attorney General "determines that" Engel v. Vitale had been overturned, The Mississippi AG could simply lie and declare that Engel had been overturned. with no evidence whatever, (like claiming an election was "stolen") and send the matter to a series of hopefully sympathetic courts! Mississippi is not known for its adherence to the provisions of law, especially when they feel that they "have God on their side" against a helpless minority such as, for example, school children or people of color. A most recent example is the blatant abuse of Long Beach students' rights with respect to concern about illegal drugs.

When will they ever learn? When will they ever learn?

1. In God We Trust, edited by Norman Cousins, p. 42. Quoted from: Peter Marshall, Jr., The Light and the Glory (Old Tappan, NJ: Flemming H. Revell, 1977) 342-343.

2. Stewart Robb, In Defense of School Prayer (Santa Ana, CA: Parca Publishing Co., 1985), 7.

3. The Antifederalists were the political group who did not want a strong federal government because they did not want the authority of the states to be usurped. The debate about whether or not to have a federal Constitution had raged between the Federalists and the Antifederalists.

4. See the dissension opinion of Justice William Rehnquist in Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 U.S. 38 (1985) 94, and the majority opinion in King v. Village of Waunakee, 185 Wis.2d (1994) 25 or 517 NW.2d (1994) 671.

5. The letter was addressed "To Thomas Jefferson, President of the United States of America," from the "Danbury Baptist Association, in the State of Connecticut, assembled October 7th 1801." A microfilm copy was obtained from the Manuscript Room of the Library of Congress. #20111. The author then worked from the original document, held by the Library of Congress.

6. This letter was addressed to Messrs. Nehemiah Dodge, Ephraim Robbins, and Stephen S. Nelson, on January 1, 1802. Adrienne Koch and William Peden, The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson (New York, NY: Random House, 1944), 307.

7. This wording exists in an earlier draft of Jefferson's letter, obtained from the Manuscript Room of the Library of Congress. #20593. Copied from Microfilm. The paragraph went on to address the concept of a national church, and note that religious exercises should only be subject to "the voluntary regulations and discipline of each respective sect." A note written on the document says that this paragraph was omitted to avoid misinterpretation by "some of our republican friends in the eastern states."

8. Inauguration Address, given on March 4, 1801. Ibid, 297.

9. The Northwest Ordinance was originally passed by the First Continental Congress, and again by the Congress of the post-Revolutionary War. Robb, 22.

10. Robb, 31.

11. See Craig L. Parshall, Esq., The Necessity For, and the Elements of a Constitutional Amendment Protecting Prayer and Other Acknowledgments of God In Our Public Schools, 1994.

12. The sample was of 1205 people -- 577 men and 628 women. The religious affiliations were 41 percent Protestant, 28 percent Catholic, 1 percent Jewish, 1 percent other Christian, and 23 percent other faiths. Two percent fell into the "Don't Know" category. [George Barna, Absolute Confusion: How Our Moral and Spiritual Foundations Are Eroding In This Age of Change (Ventura, CA: Regal Books, 1993), 282.] Another recent poll (USA Today/CNN/Gallup) shows that 96 percent of Americans "believe in God." [Leslie Miller, USA Today, 22 December 1994.]

13. Ibid, 274.

14. Herbert W. Titus, A Winning Strategy to Restore Prayer to the Public Schools, Regent University Law Review, Vol. I, No. 1, Spring 1991. Taken from Lawrence Tribe, American Constitutional Law 1170 (2d ed. 1988).

15. Ibid, according to Titus.

16. Any form of speech, including prayer, that is an activity that might be physically harmful to students or disruptive to the operation of the school would be restricted by constitutional "manner" provisions. That would, for example, preclude a student from enacting a religious ritual that would bring physical harm to themselves, or someone else, as their form of "prayer."

17. The Sources of Our Liberties, Ed. Richard L. Perry (Chicago, IL: The American Bar Foundation, 1978), 416.

18. The significance of the Constitution's Subscription Clause is noted by constitutional lawyer and scholar, Herbert W. Titus.