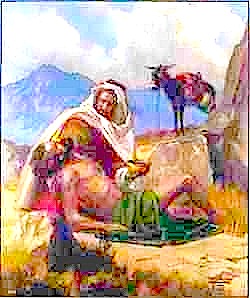

The Good Samaritan

|

|

Because he was a good neighbor, the Good Samaritan has become the most famous fictional character of all time. Possibly more people have heard about him than about Mickey Mouse! What other story has been told for over 1900 years with so memorable a character?

But to truly understand this story, to fully appreciate its significance, we have to go back to the time and place, to the culture and society in which the story was told. We have to read between the lines what the hearers would have assumed or understood. Only there can we find the true meaning and significance of this remarkable story.

The setting for the story is in response to a question by an unidentified lawyer, a teacher of the Jewish Law, who, Luke tells us, tried to test Jesus with the question "what must I do to inherit eternal life?" The question was not an idle one, for the Jewish tradition contained 613 laws, 248 acts which were commanded, and 365 which were forbidden. Only the lawyers, the Pharisees, the experts in the Law, could remember them all, and not even they found it possible to observe each and every one. Jesus often criticized the Pharisees for their inappropriate priorities, by which they emphasized the letter of the Law over the spirit and concern for their fellow men.

So the question was appropriate; "What do I have to do," and what can I safely ignore? But, as Luke observes, the question was a trap. Whatever law Jesus picked, he would be implicitly denying the other 612.

Jesus doesn't fall for the trap. Instead, he turns the tables on the lawyer; hoisting him on his own petard. He turns the question back for the lawyer to define for himself what he needed to do for eternal life, "Well, what do you think? How do you interpret the Scriptures?"

The lawyer doesn't fall for the trap, either. Instead, he replies with what was, at the time, a fairly standard response, "You shall love the Lord, your God, with all your heart, with all your being, with all your strength, and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself." We find that it was a principle recognized as the summation of all of the Jewish laws in Matthew 22:34 ff and Mark 12:28 ff. Jesus affirms the response. "Yes," he agrees. "Do this and you will live."

But this answer, the only one possible, put the lawyers in a very bad light, for ignoring their neighbors and placing emphasis on ritual was precisely the fault Jesus found with them (Matthew 23:13-26, Luke 11:42-46). So the lawyer tries to salvage the situation by demanding, as lawyers often do, to know the precise definition of the term, "neighbor." The lawyer's next door neighbors were probably men like himself, whom he would not have too much difficulty loving.

Again, Jesus does not answer the question. Instead, as he was so fond of doing, he illustrates his teaching with a story.

The road from Jerusalem to Jericho is as old as human history. It is the main road from the ports on the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea to the trade routes of the Middle East. It runs about 15 miles from the hill country of Judea, where Jerusalem and Bethlehem are located, along progressively more mountainous terrain, through a natural cleft in the mountains, down into the plain of the Jordan River basin. It is one of the most desolate places on earth, an evil place, the wilderness where John the Baptist lived, into which Jesus was driven for 40 days and nights to be tempted by Satan. From low earth orbit, the break in the mountains through which this route runs is clearly visible. The muted greens and greys of the hill country, where Jerusalem is located, give way to the stark sandy browns of lifeless desert. Those of you who saw, "Jesus Christ, Superstar," will remember the location of the movie as similar to this terrain. It is hot, dry and barren, where the mountains on either side provide a perfect vantage point for the murderer and outlaw to plan and execute an ambush of the frequent treasure convoys, and the scavengers are always hungry.

|

| Google image of the location of the ancient Jericho Road |

|---|

The implication of "a man" in the story would strongly suggest that the traveler was alone, an almost criminal act of foolhardiness. There might have been good reasons for him being alone, but the hearers may well have thought he got his just deserts by being waylaid by robbers, considering it the wages of sin, by which God, in the form of nature, tends to remove from the human gene pool people who are prone to acts of culpable stupidity.

Whatever the victim tried to do to save himself, it didn't work! The robbers ambushed him, beat him senseless, and took everything he had, including his clothes. The condition of the man can be variously translated as, "half dead," "as if he were dead," "as dead," "almost dead," or "to die." In any event, he was obviously in a very bad way. From all outward appearances, the man had already died.

So the priest and Levite came along and saw this "corpse" lying by the side of the road. These were rich and influential men, and they were most certainly traveling by large caravan. Had they stopped, they would have had either to stop the entire caravan, putting everyone at risk from the robbers who had already committed one act of mayhem, or else they would have had to let the caravan go on without them, thus putting themselves at unacceptable risk.

But there is another element here that many people today may not recognize. These were not just religious leaders, they were the scholars, schoolteachers, doctors, lawyers, librarians, journalists, news commentators, justices of the peace, and advisors to the lovelorn of the communities they served. And to do their jobs, on which the welfare of their communities depended, they had to maintain ritual purity. They had to scrupulously avoid doing anything which would make them "unclean." And there is nothing that can make a person unclean faster than messing with a dead body (See Numbers 19:11 and following). So these men were not being cruel or heartless, they were being prudent and practical.

The man was dead.

There was nothing they could do for him.

Chicken soup wouldn't have helped!

...And the scavengers were always hungry!

Up to this point, the story wasn't very interesting. People were getting waylaid on this road all the time. That's why they traveled in large, well armed groups.

The Samaritan introduces an element of surprise. Samaria was a rich and powerful kingdom, but it was far to the north, just this side of Galilee. The Samaritan was a foreigner, an unlikely wayfarer on this particular road. Moreover, the Samaritans were hated and despised by the people of Judea, who considered them second-class half-breeds, if that. That's why the Samaritan couldn't find anyone to travel with him. We are told in John 4:7 ff that on a trip through Samaria, a woman at Jacob's well was shocked that a Jew would even speak to a Samaritan, let alone ask her for a drink of water on a hot day.

So it was a surprise for the Samaritan to be there at all, much less to take pity on the hapless victim. By rights, he would have been expected also to pass him by, for reasons which were quite different than those of the priest and the Levite. The hearers of this story might have attributed base motives for the Samaritan's behavior.

"Of course, a Samaritan wouldn't be concerned about being unclean."

"Maybe he was looking to steal some booty the robbers had left."

"Perhaps the stupid oaf was just curious, and stopped to have a look around in this dangerous place, where the robbers had already claimed one victim."

"%&!#$%@# Samaritan!"

But for whatever reason, the Samaritan stopped to investigate and found that, to his surprise, the victim was still alive!

What to do?

Because he was a good neighbor, the Samaritan saved the almost dead victim. He did what any reasonable person would have done, what we, and the priest and Levite (had they known the man was still alive) would probably have done also. Because he was a good neighbor, he gave the victim what first aid he could, hoisted him on his camel or donkey, and took him to a hospital. Of course, they didn't have hospitals then, but the "inn" was a place of comfort and rest for weary travelers, and would have been the appropriate place to take someone who didn't appear to have anyone else to look after him. The victim, of course, did absolutely nothing, and was probably unconscious for most of the encounter. Luke says that the Samaritan personally took care of him.

(The word "inn" is actually an English translation of the Latin "stabulum," from which we get the English word "stable." "Inn" is a British word for an essentially British invention, the bed and breakfast hotel. There is reason to believe that the "inn" to which the Samaritan would have taken the hapless victim was actually what today we would call a "boarding stable." There the unlucky fellow could curl up and sleep in the warm hay, and there would be someone on watch used to tending sick or injured animals who would be able to suture up his wounds, apply bandages, splints and poultices, provide food and water, and otherwise look after him. It would have been common practice, as it was in the US Old West eighteen centuries later, for the proprietor to accept payment up front and agree to settle the final account later, when the customer was planning to return.)

But then, because he was a good neighbor, the Samaritan does something very strange! Not only does he pay the victim's medical bill and guarantee payment for any future expenses, but, because he was a good neighbor, he leaves the man at the "inn!" By rights, the robbery victim owed his life to the Samaritan, and would have been expected to serve him as a slave for the rest of his life. But the Samaritan forgives the debt, and goes on his way, leaving the robbery victim a free man. It is this act, perhaps much more than the care given the man, which was recognized by the lawyer as an act of mercy (Latin: misericordiam) on the part of the Samaritan.

This is the often overlooked element of this story, cleverly woven into an explanation of what "love thy neighbor" means by a man who was also God. It is, in fact, the allegory between the Samaritan and God, who saves us from death and takes care of all our needs as a good neighbor, but also shows us mercy and forgives our debt to him as well. We are given the freedom to do as we please, but not before we receive all we need to survive in this hostile world.

So the next question asked is, in a sense, a puzzle. The Samaritan was clearly NOT the victim's neighbor. He was a foreigner. The right answer to the question, "Which of these ... was neighbor to the robbers' victim?" was obviously that the priest and Levite were neighbors, and the Samaritan was not. Yet that is clearly not the point of the story. Because he was a good neighbor, the Samaritan saw the potential for life in the victim, and treated him with love and respect, like a neighbor, not a corpse or a slave. It was not circumstance, or geography, or the Law that decided who was the neighbor, it was the willful and conscious decision of the Samaritan to treat the other as one of his own.

This is, in fact, the essence of the Christian relationship with God. We all know the Christmas story in Luke 2:1-20, but there is a Christmas story in John as well. John tells us in John 1:14 that God, the "Word", "became flesh. and made his dwelling among us," essentially becoming our neighbor. Indeed, Jesus tells us that the criteria by which we will be judged is whether we treat others as our neighbors, as stated in Matthew 25:31-46. As Jesus said in Luke 10:28, "do this and you will live."

From a 4th century population of 1.2 million, today there are only about 800 Samaritans in the entire world. At the beginning of the last century, there were less than 150 of them. (See the information below.) If they were animals, such as mountain gorillas, they would surely be on the endangered species list. But because they are people, and dispossessed people at that, few care about them. The Palestinians consider them Israelis, and the Israelis consider them Palestinians. Every year, about half of them have to brave the trek from Holon, outside of Tel Aviv, across the Palestinian border to Mount Gerizim on the West Bank to observe their traditional Passover rituals. Nevertheless their fortunes have improved in recent years, and except for the fact that half of them live in Israel and half of them live in the Palestinian autonomy, they are not too badly off, as things in that area of the world are measured.

But they are not particularly well known, either. Few Christians today would be able to say much about them, or be able to locate their homes on a map. Yet everyone knows what a "Good Samaritan" is. The fictional character of this story has been known for almost 20 centuries. He is the most famous fictional character of all time....

not because he was a rich man,

or a famous man,

or an influential man,

or a powerful man,

and not even because he was a particularly good man;

but because...

he was...

a good...

neighbor!

By Dana Rosenblatt (Special to CNN) Monday, October 14, 2002 Posted: 5:38 PM EDT (2138 GMT)

HOLON, Israel (CNN) -- Every Thursday, Benyamim Tsedaka prepares for his weekly visit to the West Bank for the Sabbath.

Armed with coffee mug and cell phone, the newspaper editor departs his home in Holon for the lush hills of Mount Gerizim, near Nablus.

There, he'll gather with friends and family and relinquish his casual button-down shirt and jeans to don the flowing white robe and red headdress that is traditional to the Samaritan Sabbath.

Despite their ties to both sides of the border that separates Israel and the Palestinian territories, Tsedaka and the people in his community are a distinct group, neither Jewish nor Arab.

They are Samaritans, members of a culture whose roots also reach back into Biblical times.

Samaritans are descendants of the ancient Israelites who broke from Judaism some 2,200 years ago and were centered mainly in and around the region of Samaria -- now a part of the West Bank.

Even today, many people associate the group with the parable of the "Good Samaritan" from the New Testament, and the term is often used to describe a person who helps another unselfishly.

In modern times, as they try to maintain their distinct cultural identity, the Samaritans find themselves caught in the middle of the decades-long conflict between Israelis and Palestinians.

"We are in the heart of the problem, trying to find ways to exist with both," says Tsedaka.

Their community numbers less than 700 people and is split almost evenly between the Palestinian controlled area of Mount Gerizim in the West Bank and the Israeli town of Holon near Tel Aviv.

The Samaritans are Israeli citizens and recognized as Jews according to the Law of Return. Yet, those who live in the West Bank also are represented in the Palestinian legislature. Palestinians commonly refer to them as "Jews of Palestine." Overall, they seek to maintain neutrality between both sides.

As a people, they are united by a common religion, tradition and language. They are one of a few remaining cultures that speak, read and write the ancient Hebrew language, Aramaic.

They have vowed to keep the language and culture alive for centuries to come, though they speak modern Hebrew and Arabic in daily conversation.

In fact, Aramaic is one of four languages -- along with Arabic, modern Hebrew and English -- that are used in Tsedaka's community newspaper, A.B. - The Samaritan News, which he edits and publishes every two weeks.

The religious practices followed by Samaritans are closely related to Judaism.

Although their calendar is slightly different from the Jewish calendar, they celebrate Yom Kippur (the day of atonement) and Passover, traditionally marked by the sacrifice of a lamb at Mount Gerizim.

Unlike the Jews, however, the Samaritans do not celebrate Hanukkah or Purim. Religious ceremonies are led by a Samaritan high priest and recited in Aramaic.

Despite their acceptance by both the Israelis and Palestinians, the Samaritans have not been untouched by the troubles in their native land.

Before the first Palestinian intifada broke out in 1987, a small number of Samaritans lived comfortably alongside the Palestinians in Nablus. A year after the uprising, they sought the nearby refuge of Mount Gerizim, the place where, according to the Bible, Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son.

Still, Nablus remains the cultural and economic center for the Samaritans of Mount Gerizim. There, they attend public schools and universities, and hold positions in the Palestinian ministry.

"The Samaritans of Nablus are Palestinian citizens, with the same rights and obligations," says Ghassan Shaka, mayor of Nablus. "They are part of us ... the same feelings, the same hopes, and the same destiny."

In 1996, Palestinian Authority President Yasser Arafat granted the Samaritans a seat on the 88-member Palestinian Legislative Council.

At the same time, because they are Israeli citizens, the Samaritans from Holon are required to serve in Israel's military, a calling many of them heed with pride.

"A lot of people try not to serve in the Israeli army. But you will not find any of those to be Samaritan," says Tsedaka, whose 18-year-old son serves in the Israel Defense Forces. "For us it is a great honor."

Though they acknowledged the irony of holding a Palestinian legislative seat while many of their members also serve in Israel's army, the Samaritans were keen to accept the offer.

"We don't ask why. ... When he [Arafat] first mentioned the idea ... we were happy to," Tsedaka says.

The Samaritans of Mount Gerizim are faced with the toughest challenges, says Daphna Tsimcchoni, a researcher at the Truman Institute for Peace at Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

"In the West Bank, they are caught between the Israeli army and the Palestinian population. They must remain neutral in the face of Palestinian and Israeli politics, differentiating from the two sides, and also their neighbors, Jewish settlers."

The Jewish settlement of Bracha, next to the Samaritan neighborhood, has been the target of several attacks from Palestinian militants.

Israel maintains a constant military presence in the area to ensure the security of the settlement and monitor Palestinian movement in and out of Nablus.

The Israeli military says the Samaritans pose no threat to the area and even serve as a peaceful buffer. But for the Samaritans, living in a militarized zone is not without hardship.

"The Samaritans know the value of having the IDF there, but on the other hand," says Tsedaka, "They are suffering from the situation."

Samaritans say the tanks have destroyed the sanctity of their neighborhood, making life unbearable.

"No one will help us," says Joseph Cohen, a Samaritan of Mount Gerizim. "The tanks remain in our front yard, and create dust and mess. When it rains, the mud is so bad, our children can't even go to school."

Beyond the inconvenience, transit through the Green Line, the border that separates Israel from the West Bank, can prove perilous, as Cohen lived to tell.

Last year, the father of three took an alternate route home on a road to Bracha.

He was ambushed by a group of Palestinian militants who mistook him for a settler, he says. Severely wounded, Cohen lost control of the car and rammed through an Israeli roadblock. Israeli soldiers took him for a terrorist and they, too, shot at him.

Left unable to walk without the aid of crutches, Cohen receives a small pension from the Israeli government for his wounds. But he says the money is not enough.

"We live here in a jungle," says Cohen. "I love the country of Israel. I know they have their own problems, but they need to pay attention to us. "

Asked if he would ever leave the mountain, Cohen remains adamant.

"We will not leave. This is our home."

The Samaritans' cultural roots are in Samaria, in today's northern West Bank.

Religious practices are similar to Judaism, though calendar is slightly different.

In the 4th century, Samaritan population reached 1.2 million. It dwindled to 146 people by 1917.

As of January 2002, 330 Samaritans lived in Holon near Tel Aviv and 320 in Mount Gerizim in the West Bank.

by Rhonda Vincent and The Rage

Samaritan Studies newspaper

editor Dr. Benyamin Tsadaka

synagogue in Holon, decorated

with a menorah and Aramaic scriptAmid Conflict, Samaritans Keep Unique Identity

Neither Jew Nor Muslim

A People Divided

FACT BOX

Title page of a Holon Samaritan calendar for the years 2003-2004